Laura Wilder (1867 – 1957)

Laura Ingalls Wilder (February 7, 1867 - February 10, 1957) was an American author.

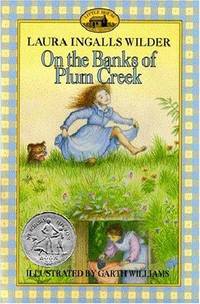

She authored the series of historical fiction books for children based on her childhood in a pioneer family. The most well-known of her books is Little House on the Prairie.

Laura Ingalls Wilder was born in Wisconsin to parents Charles Phillip and Caroline Lake (Quiner) Ingalls. She was the second of five children. The details of her family life through adolescence are chronicled in her semi-autobiographical "Little House" books. As her books reveal, she and her family moved extensively throughout the mid-west during her childhood. Although she was a bright student, her education was rather sporadic, a result of her family often living in isolated areas where schools were not yet established, or the family's finances resulting in Laura interrupting her schooling to earn money. The family eventually settled in De Smet, Dakota Territory, where she attended school more regularly and worked as a seamstress and teacher before she married homesteader Almanzo James Wilder (1857–1949) in 1885. She had two children: the novelist, journalist and political theorist Rose Wilder Lane (1886–1968), and an unnamed son, who died soon after birth in 1889.

In the late 1880s, complications from a life-threatening bout of diphtheria left Almanzo partially paralyzed. While he eventually regained nearly full use of his legs, he needed a cane to walk for the remainder of his life. This setback began a series of disastrous events that included the death of their unnamed newborn son, the destruction of their home and barn by fire and several years of severe drought that left them in debt, physically ill and unable to earn a living from their 320 acres (1.3 km²) of prairie land.

In about 1890, the Wilders left South Dakota and spent about a year resting at Almanzo's parents' prosperous Minnesota farm, before moving briefly to Florida. The Florida climate was sought to improve Almanzo's health, but Laura, used to living on the dry plains, wilted in the heat and southern humidity. They soon returned to De Smet and purchased a small house in town. The Wilders received special permission to start precocious Rose in school early, and took jobs (Almanzo as a day laborer, Laura as a seamstress at a dressmaker's shop) to save enough money to once again start up a farming operation.

n 1894, the hard-pressed young couple moved a final time to Mansfield, Missouri, making a partial down payment on a piece of undeveloped property just outside town that they named Rocky Ridge Farm. What began as about 40 acres (0.2 km²) of thickly wooded, stone covered hillside with a windowless log cabin, over the next 20 years, evolved into a 200 acre (0.8 km²), relatively prosperous, poultry, dairy and fruit farm. The ramshackle log cabin was eventually replaced with an impressive and unique ten-room farmhouse and outbuildings.

The couple's climb to financial security was a slow and halting process. Initially, the only income the farm produced was from wagonloads of firewood Almanzo sold for fifty cents in town, the result of the backbreaking work of clearing the trees and stones from land that slowly evolved into fertile fields and pastures. The apple trees would not begin to bear fruit for seven years. Barely able to eke out a more than a subsistence living on the new farm, the Wilders decided to move into nearby Mansfield in the late 1890s. Almanzo found work as an oil salesman and general delivery man, while Laura took in boarders and served meals to local railroad workers. Any spare time was spent improving the farm and planning for a better future.

Rose Wilder Lane grew into an intelligent, restless young woman who was not satisfied with the rural lifestyle her parents loved. She later described her unhappiness and isolation at the Mansfield school,attributing it to a combination of her family's poverty and her reputation as an outstanding scholar. By the time she was sixteen, dissatisfaction with the limited curriculum available in Mansfield resulted in Rose being sent to spend a year with her aunt, Eliza Jane Wilder, in Crowley, Louisiana, to attend a more advanced high school there. She graduated with distinction in 1904 and soon returned to Mansfield. The Wilders' financial situation, while somewhat improved by this time, still placed higher education out of the question for Rose. Taking matters into her own hands, Rose learned telegraphy at the Mansfield depot and soon departed Mansfield for Kansas City, where she landed a job with Western Union as a telegraph operator. In 1904, it was uncommon for a seventeen-year-old girl to leave home to work for a living, but her parents recognized that their daughter was not cut out for the typical options that life offered to girls who remained in Mansfield: housewife or spinster. A remarkable transformation occurred in the ensuing years, and Rose Wilder Lane became a well-known, if not famous, literary figure of her day. She was the most famous person to hail from Mansfield, Missouri, until Laura Ingalls Wilder began to publish her "Little House" Books in the 1930s.

Meanwhile, by 1910, Rocky Ridge Farm was established to the point where Laura and Almanzo returned there to focus their efforts on increasing the farm's productivity and output. The impressive 10 room farmhouse completed in 1912 stand a testament to their labors and determination to carve a comfortable and attractive home from the land. Having learned a hard lesson from focusing solely on wheat farming in South Dakota, the Wilders' Rocky Ridge Farm became a diversified poultry and dairy farm, as well as boasting an abundant apple orchard. Laura, always active in various clubs and an advocate for several regional farm associations, was recognized as an authority in poultry farming and rural living, which led to invitations to speak to groups around the region. Following Rose's developing writing career also inspired her to do some writing of her own. An invitation to submit an article to the Missouri Ruralist in 1911 led to a permanent position as an columnist and editor with that publication — a position she held until the mid-1920s. She also took a paid position with a Farm Loan Association, dispensing small loans to local farmers from her office in the farmhouse. Her column in the Ruralist, "As a Farm Woman Thinks", introduced Mrs. A.J. Wilder to a loyal audience of rural Ozarkians, who enjoyed her regular columns, which ranged in topic from home and family, World War I and other world events, to the fascinating world travels of her daughter and her own thoughts on the increasing options being offered to women during this era.

While the Wilders were never wealthy until the Little House series of books began to achieve popularity, the farming operation and Laura's income from writing and the Farm Loan Association provided a stable enough living for the Wilders to finally place themselves in Mansfield middle-class society. Laura's fellow clubwomen were mostly the wives of business owners, doctors and lawyers, and her club activities took up much of the time that Rose was encouraging her to use to develop a writing career for national magazines, as Rose had done. Laura seemed unable or unwilling to make the leap from writing for the Missouri Ruralist to these higher-paying national markets. The few articles she was able to sell to national magazines were heavily edited by Rose and placed solely through Rose's established publishing connections.

During much of the 1920s and 1930s, between long stints living abroad (including in her beloved adopted country of Albania), Rose lived with her parents at Rocky Ridge Farm. As her free-lance writing career flourished, Rose successfully invested in the booming Stock Market. Her newfound financial freedom led her to increasingly assume responsibility for her aging parents' support, as well as providing for the college educations of several young people she "adopted" both in Albania and Mansfield. She encouraged her parents to scale back the farming operation, bought them their first automobile and taught them both how to drive. Rose also took over the farmhouse her parents had built and had a beautiful, modern stone cottage built for them. Around 1928, Laura stopped writing for the Missouri Ruralist and resigned from her position with the Farm Loan Association. Hired help was installed in another new house on the property, to take care of the farm work that Almanzo, now in his 70s, could not easily manage. A comfortable and worry-free retirement seemed possible for Laura and Almanzo until the Stock Market Crash of 1929 wiped out the family's investments (Laura and Almanzo still owned the 200 acre (800,000 m²) farm, but they had invested most of their hard-won savings with Rose's broker). Rose was faced with the grim prospect of selling enough of her writing in a depressed market to maintain the responsibilities she had assumed. Laura and Almanzo were faced with the fact that they were now dependent on Rose as their primary source of support.

In 1930, Laura asked her daughter's opinion about a biographical manuscript she had written about her pioneering childhood. The Great Depression, coupled with the recent deaths of her mother and her sister Mary, seem to have prompted her to preserve her memories in a "life story" called "Pioneer Girl". She had also renewed her interest in writing in the hope of generating some income. Little did either of them realize that Laura Ingalls Wilder, 63, was about to embark on an entirely new career: writer of books for children.

Controversy surrounds Rose's exact role in what became her mother's famous "Little House" series of books. Some argue that Laura was an "untutored genius," relying on her daughter mainly for some early encouragement and her connections with publishers and literary agents. Others contend that Rose basically took each of her mother's unpolished rough drafts in hand and completely (and silently) transformed them into the series of books we know today. The truth most likely lies somewhere between these two positions — Laura's writing career as a rural journalist and credible essayist began more than two decades before the "Little House" series, and Rose's formidable skills as an editor and ghostwriter, are well-documented.

The existing evidence (including ongoing correspondence between the women concerning the development of the series, Rose's extensive personal diaries and Laura's draft manuscripts) tends to reveal an ongoing joint collaboration. The conclusion can be drawn that Laura's strengths as a compelling storyteller and Rose's considerable skills in dramatic pacing and literary structure contributed to an occasionally tense, but fruitful, collaboration between two talented and headstrong women. In fact, the collaboration seems to have worked both ways: two of Rose's most successful novels, Let the Hurricane Roar

Laura Ingalls Wilder was born in Wisconsin to parents Charles Phillip and Caroline Lake (Quiner) Ingalls. She was the second of five children. The details of her family life through adolescence are chronicled in her semi-autobiographical "Little House" books. As her books reveal, she and her family moved extensively throughout the mid-west during her childhood. Although she was a bright student, her education was rather sporadic, a result of her family often living in isolated areas where schools were not yet established, or the family's finances resulting in Laura interrupting her schooling to earn money. The family eventually settled in De Smet, Dakota Territory, where she attended school more regularly and worked as a seamstress and teacher before she married homesteader Almanzo James Wilder (1857–1949) in 1885. She had two children: the novelist, journalist and political theorist Rose Wilder Lane (1886–1968), and an unnamed son, who died soon after birth in 1889.

In the late 1880s, complications from a life-threatening bout of diphtheria left Almanzo partially paralyzed. While he eventually regained nearly full use of his legs, he needed a cane to walk for the remainder of his life. This setback began a series of disastrous events that included the death of their unnamed newborn son, the destruction of their home and barn by fire and several years of severe drought that left them in debt, physically ill and unable to earn a living from their 320 acres (1.3 km²) of prairie land.

In about 1890, the Wilders left South Dakota and spent about a year resting at Almanzo's parents' prosperous Minnesota farm, before moving briefly to Florida. The Florida climate was sought to improve Almanzo's health, but Laura, used to living on the dry plains, wilted in the heat and southern humidity. They soon returned to De Smet and purchased a small house in town. The Wilders received special permission to start precocious Rose in school early, and took jobs (Almanzo as a day laborer, Laura as a seamstress at a dressmaker's shop) to save enough money to once again start up a farming operation.

n 1894, the hard-pressed young couple moved a final time to Mansfield, Missouri, making a partial down payment on a piece of undeveloped property just outside town that they named Rocky Ridge Farm. What began as about 40 acres (0.2 km²) of thickly wooded, stone covered hillside with a windowless log cabin, over the next 20 years, evolved into a 200 acre (0.8 km²), relatively prosperous, poultry, dairy and fruit farm. The ramshackle log cabin was eventually replaced with an impressive and unique ten-room farmhouse and outbuildings.

The couple's climb to financial security was a slow and halting process. Initially, the only income the farm produced was from wagonloads of firewood Almanzo sold for fifty cents in town, the result of the backbreaking work of clearing the trees and stones from land that slowly evolved into fertile fields and pastures. The apple trees would not begin to bear fruit for seven years. Barely able to eke out a more than a subsistence living on the new farm, the Wilders decided to move into nearby Mansfield in the late 1890s. Almanzo found work as an oil salesman and general delivery man, while Laura took in boarders and served meals to local railroad workers. Any spare time was spent improving the farm and planning for a better future.

Rose Wilder Lane grew into an intelligent, restless young woman who was not satisfied with the rural lifestyle her parents loved. She later described her unhappiness and isolation at the Mansfield school,attributing it to a combination of her family's poverty and her reputation as an outstanding scholar. By the time she was sixteen, dissatisfaction with the limited curriculum available in Mansfield resulted in Rose being sent to spend a year with her aunt, Eliza Jane Wilder, in Crowley, Louisiana, to attend a more advanced high school there. She graduated with distinction in 1904 and soon returned to Mansfield. The Wilders' financial situation, while somewhat improved by this time, still placed higher education out of the question for Rose. Taking matters into her own hands, Rose learned telegraphy at the Mansfield depot and soon departed Mansfield for Kansas City, where she landed a job with Western Union as a telegraph operator. In 1904, it was uncommon for a seventeen-year-old girl to leave home to work for a living, but her parents recognized that their daughter was not cut out for the typical options that life offered to girls who remained in Mansfield: housewife or spinster. A remarkable transformation occurred in the ensuing years, and Rose Wilder Lane became a well-known, if not famous, literary figure of her day. She was the most famous person to hail from Mansfield, Missouri, until Laura Ingalls Wilder began to publish her "Little House" Books in the 1930s.

Meanwhile, by 1910, Rocky Ridge Farm was established to the point where Laura and Almanzo returned there to focus their efforts on increasing the farm's productivity and output. The impressive 10 room farmhouse completed in 1912 stand a testament to their labors and determination to carve a comfortable and attractive home from the land. Having learned a hard lesson from focusing solely on wheat farming in South Dakota, the Wilders' Rocky Ridge Farm became a diversified poultry and dairy farm, as well as boasting an abundant apple orchard. Laura, always active in various clubs and an advocate for several regional farm associations, was recognized as an authority in poultry farming and rural living, which led to invitations to speak to groups around the region. Following Rose's developing writing career also inspired her to do some writing of her own. An invitation to submit an article to the Missouri Ruralist in 1911 led to a permanent position as an columnist and editor with that publication — a position she held until the mid-1920s. She also took a paid position with a Farm Loan Association, dispensing small loans to local farmers from her office in the farmhouse. Her column in the Ruralist, "As a Farm Woman Thinks", introduced Mrs. A.J. Wilder to a loyal audience of rural Ozarkians, who enjoyed her regular columns, which ranged in topic from home and family, World War I and other world events, to the fascinating world travels of her daughter and her own thoughts on the increasing options being offered to women during this era.

While the Wilders were never wealthy until the Little House series of books began to achieve popularity, the farming operation and Laura's income from writing and the Farm Loan Association provided a stable enough living for the Wilders to finally place themselves in Mansfield middle-class society. Laura's fellow clubwomen were mostly the wives of business owners, doctors and lawyers, and her club activities took up much of the time that Rose was encouraging her to use to develop a writing career for national magazines, as Rose had done. Laura seemed unable or unwilling to make the leap from writing for the Missouri Ruralist to these higher-paying national markets. The few articles she was able to sell to national magazines were heavily edited by Rose and placed solely through Rose's established publishing connections.

During much of the 1920s and 1930s, between long stints living abroad (including in her beloved adopted country of Albania), Rose lived with her parents at Rocky Ridge Farm. As her free-lance writing career flourished, Rose successfully invested in the booming Stock Market. Her newfound financial freedom led her to increasingly assume responsibility for her aging parents' support, as well as providing for the college educations of several young people she "adopted" both in Albania and Mansfield. She encouraged her parents to scale back the farming operation, bought them their first automobile and taught them both how to drive. Rose also took over the farmhouse her parents had built and had a beautiful, modern stone cottage built for them. Around 1928, Laura stopped writing for the Missouri Ruralist and resigned from her position with the Farm Loan Association. Hired help was installed in another new house on the property, to take care of the farm work that Almanzo, now in his 70s, could not easily manage. A comfortable and worry-free retirement seemed possible for Laura and Almanzo until the Stock Market Crash of 1929 wiped out the family's investments (Laura and Almanzo still owned the 200 acre (800,000 m²) farm, but they had invested most of their hard-won savings with Rose's broker). Rose was faced with the grim prospect of selling enough of her writing in a depressed market to maintain the responsibilities she had assumed. Laura and Almanzo were faced with the fact that they were now dependent on Rose as their primary source of support.

In 1930, Laura asked her daughter's opinion about a biographical manuscript she had written about her pioneering childhood. The Great Depression, coupled with the recent deaths of her mother and her sister Mary, seem to have prompted her to preserve her memories in a "life story" called "Pioneer Girl". She had also renewed her interest in writing in the hope of generating some income. Little did either of them realize that Laura Ingalls Wilder, 63, was about to embark on an entirely new career: writer of books for children.

Controversy surrounds Rose's exact role in what became her mother's famous "Little House" series of books. Some argue that Laura was an "untutored genius," relying on her daughter mainly for some early encouragement and her connections with publishers and literary agents. Others contend that Rose basically took each of her mother's unpolished rough drafts in hand and completely (and silently) transformed them into the series of books we know today. The truth most likely lies somewhere between these two positions — Laura's writing career as a rural journalist and credible essayist began more than two decades before the "Little House" series, and Rose's formidable skills as an editor and ghostwriter, are well-documented.

The existing evidence (including ongoing correspondence between the women concerning the development of the series, Rose's extensive personal diaries and Laura's draft manuscripts) tends to reveal an ongoing joint collaboration. The conclusion can be drawn that Laura's strengths as a compelling storyteller and Rose's considerable skills in dramatic pacing and literary structure contributed to an occasionally tense, but fruitful, collaboration between two talented and headstrong women. In fact, the collaboration seems to have worked both ways: two of Rose's most successful novels, Let the Hurricane Roar