by Mark Stueve, Old Erie Street Books

I was never really much of a Beatles fan, though their two-minute, fifteen-second Lennon and McCartney ditty “Paperback Writer” seems to capture the general public opinion concerning the hardcover book’s poor cousin: the paperback.

More likely than not you have heard the tune–a rather wonky musical prowl about a wannabe writer of paperbacks who begs the listener “to read his book, based on a novel by a man named Lear/It’s a dirty story of a dirty man.” Yes, paperbacks: graphic, smutty, racy, lurid. All of these adjectives fit the part of the mid-twentieth century idea of a mass market paperback. Not only was it an affordable avenue to the haughty realm of literature in a less ostentatious package than their grown-up hardcover elders, the paperback of today owes its origin to the early nineteenth century and the publishing firm of one Karl Christoph Traugott Tauchnitz who offered affordable Greek and Roman classics in a novel paper-covered format. To merely state that Mister Tauchnitz started a major publishing revolution and bookselling trend would be an understatement. That contemporary copy of Homer that shares space in today’s students’ knapsacks has more in common with Tauchnitz than Aldus Manutius, whose Aldine Press with its famous anchor and dolphin device, printed inexpensive type-set versions of Greek and Latin classics in the late-fifteenth and early-sixteenth century. The Aldine imprints are masterpeices in typography; most examples of the Tauchnitz imprints I have encountered are not at all “easy on the eyes.”

For many years to follow paperbacks lived on the cheap side of the street, and it was in my youth that I first heard the superlative stated with a rather smug air that “True gentlemen have hardbound books on their shelves.” Of course I figured out immediately that though these hardcover and leather-bound books might live on a gentleman’s shelf, no guarantee exists that they actually read them. Hardcover books are equated with prosperity and propriety. By the early 1940s, paperback books were step-children of the hardcover, owed to their racy, full-color covers depicting all forms of depraved characters and events in a lurid graphic fashion. Wartime rations of paper and allied printing materials conspired to make hardcover books cheaper articles of commerce aesthetically, and paperbacks, owing to their much cheaper price point, became more acceptable in the emerging modern world.

Today, prime examples of these mass market pocket-sized gems are collected on the merit of their cover artwork. High prices are paid by serious collectors of this “cover art.” Fine condition copies of these fragile transitory paperback books fetch the bigger price. Other undervalues and still accessible areas of paperback book collecting still exist. The following topics seem worthy of mention in this light. Nonfiction titles in the areas of sports, culinary and beverage, outdoors, politics, and trendy topics of your personal choice that remain under the radar of public taste can be gathered into a collection. Foreign language paper-bound copies of your favorite collectible authors such as Hemingway or Steinbeck are still fairly common and easy to find in a large urban area. This is the material that bibliographers are aware of and are not usually that avidly pursued as the original language editions.

The important trick in collecting paperbacks is to use your cognitive prowess, looking ahead enough to purchase the materials you desire and believing in their market popularity. Pamphlets, Armed Services Editions, monographs, off-prints, chapbooks, manufacturer catalogues, fanzines, and the occasional self-published rant or cookbook seem to hold value if their content proves interesting and engaging enough. I have been gathering paper bound materials of this nature for the past thirty years, and boxing them up as a potential retirement project due to their minute size and relative ease in storage. In contrast, most paperback volumes printed by major publishers are ubiquitous and without much real character to set them apart in a positive fashion from hardcovers. Avoid these common goods at all cost unless you care to take a copy of a read along on a vacation and abandon it before your return. Having had the opportunity to purchase English language volumes throughout the world in this fashion while vacationing is a real treat. Every bibliophilic traveler will tell you that the urge to purchase books does not disappear while on another continent.

In my thirty-five years of book selling, paperbacks have proven a difficult sell for me until the advent of the Internet made me more cautious of larger-sized books which prove more expensive to ship. I have trained my eyes to respect even the lowly mass-market paper bound book, for inside its puny covers might contain a exquisite authorial signature or association. I received a customer request from Biblio this past week for a client interested in a Ken Kesey-inscribed One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest. The client passed, preferring to find a flat-signed copy, not an inscribed copy by Kesey. Most days I still have to force myself to browse about these paper bound commons in search of such authorial signatures. The mimeo revolution of the post-beatnik, revolution of the 1960s still presents viable collecting opportunities. These self-published mad dashes of poetry, fiction, and radical thought were often cranked out on the mimeograph machine,stapled together and distributed in the cause of peace and love. More often than not, issued in unspecified limited editions, valuable examples of works by popular literary figures such as Charles Bukowski, D. A. Levy, and Ed Sanders exist in these rudimentary editions.

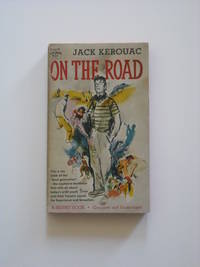

The first book that I sold was a paper-bound copy of Jack Kerouac’s On The Road. It was purchased secondhand from the budget store of Kay’s Books in downtown Cleveland in the year 1966 for one thin dime, and sold for the handsome sum of twenty-five cents to a classmate in search for Mr. Kerouac’s American fifties landscape in print. Paperback books were easier to read behind the high school text of the day, and I will admit to losing a few to eagle eyed teachers. Paperbacks are both noble and vulgar. A land where Penguin and Lion co-exist with Bantam, all the various titles shuffling about on cheap streets and rough back alleys, while bards and fools dine together.

Mark Stueve has been owner of Erie Street Bookstore since 1976, a former open shop that now deals in online sales only. Visit their Biblio bookstore page and browse their books here.

I enjoyed the article, but what does the fact that you don’t like the Beatles have to do with anything? And it’s ‘read my book,’ not ‘his,’ and ‘a dirty story about a dirty man,’ not ‘a dirty store.’

Unbound Editor’s Note: Our apologies for the error:

Excellent

Thanks for the history lesson on the origins.

I might add that, specifically in older SciFi, to list a book without naming the cover artist is really a waste of a listing.

I don’t want to sound mealy mothed but the early influence of Alan Lane/Penguin brought a huge qualitative advance in the paperback. Top artists and designers, coupled with sometimes exclusive texts, brought important ideas to a mass audience. The Booksniffer

Interesting article, and the Beatles reference shows how the paperback was still seen in the earlier 1960s.