From the publisher

For as long as accuser and accused have faced each other in public, criminal trials have been establishing far more than who did what to whom-and in this fascinating book, Sadakat Kadri surveys four thousand years of courtroom drama. A brilliantly engaging writer, Kadri journeys from the silence of ancient Egypt's Hall of the Dead to the clamor of twenty-first-century Hollywood to show how emotion and fear have inspired Western notions of justice-and the extent to which they still riddle its trials today. He explains, for example, how the jury emerged in medieval England from trials by fire and water, in which validations of vengeance were presumed to be divinely supervised, and how delusions identical to those that once sent witches to the stake were revived as accusations of Satanic child abuse during the 1980s. Lifting the lid on a particularly bizarre niche of legal history, Kadri tells how European lawyers once prosecuted animals, objects, and corpses-and argues that the same instinctive urge to punish is still apparent when a child or mentally ill defendant is accused of sufficiently heinous crimes. But Kadri's history is about aspiration as well as ignorance. He shows how principles such as the right to silence and the right to confront witnesses, hallmarks of due process guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution, were derived from the Bible by twelfth-century monks. He tells of show trials from Tudor England to Stalin's Soviet Union, but contends that no-trials, in Guantanamo Bay and elsewhere, are just as repugnant to Western traditions of justice and fairness. With governments everywhere eroding legal protections in the name of an indefinite war on terror, Kadri'sanalysis could hardly be timelier. At once encyclopedic and entertaining, comprehensive and colorful, The Trial rewards curiosity and an appreciation of the absurd but tackles as well questions that are profound. Who has the right to judge, and why? What did past civilizations hope to achieve through scapegoats and sacrifices-and to what extent are defendants still made to bear the sins of society at large? Kadri addresses such themes through scores of meticulously researched stories, all told with the verve and wit that won him one of Britain's most prestigious travel-writing awards-and in doing so, he has created a masterpiece of popular history.

Details

-

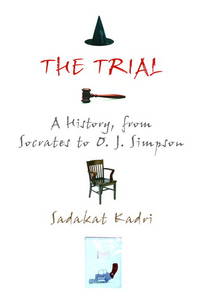

Title

The Trial A History, from Socrates to O. J. Simpson

-

Author

Sadakat Kadri

-

Binding

Hardback

-

Edition

First Thus

-

Language

EN

-

Publisher

Random House, New York

-

Date

August 30, 2005

-

ISBN

9780375505508

Excerpt

Chapter One

From Eden to Ordeals

It is only our conception of time that makes us call the Last Judgment by that name; in fact it is a permanent court-martial.

- Franz Kafka, Aphorisms

One of the few things that humanity has agreed upon for most of history is that its laws descend directly from the gods. The oldest complete legal code yet discovered, inscribed onto a black cone by the Babylonians almost four thousand years ago, shows Shamash, god of the sun, enthroned and handing down his edicts to a reverential King Hammurabi. Jehovah reportedly did much the same thing a few centuries later, carving ten commandments onto two tablets with His own finger as Moses stood by on fiery Mount Sinai. Coincidentally or otherwise, it was said of Crete’s King Minos that he climbed Mount Olympus every nine years to receive legal advice from Zeus. Ancient cultures were equally certain that the power to adjudicate breaches of the law rested ultimately in the hands of the gods. The methods of enforcement were often as terrible as they were mysterious—ranging from bolts of lightning to visitations of boils—but the justice of the punishments was as unquestionable as the law that they honored.

And yet, for all the insistence that heavenly laws were cast in stone and divine judgments unerring, one question always caused turmoil—namely, to whom, down on earth, had the right to judge been delegated? The priests who veiled their various scrolls and statutes invariably argued that only they could interpret their secrets, backing up the claim with further revelations as and when required. Monarchs were no less assertive, and constantly sought to interfere with the religious mysteries of justice. Some even argued that the power lay elsewhere. Among the Hebrews, for example, an old tradition prescribed that homicides should be tried by common people, and although Judah’s priests established something close to a theocracy after 722 b.c., their oldest myth of all characterized the ability to tell good from evil as every human being’s birthright. The story of the Fall was not, admittedly, a ringing endorsement of the power to judge—Adam and Eve had, after all, paid for their apple with sorrow, sweat, and death—but it was certainly a start.

The Athenians would produce a considerably more robust illustration of humanity’s inherent sense of justice: Aeschylus’ Oresteia, the oldest known courtroom drama in history. The trilogy, first performed in 458 b.c., retells the ancient myth of Orestes, scion of the royal house of Atreus—a bloodline as polluted as any that has managed to perpetuate itself on this earth. The corruption had set in when its founding father, Tantalus, chose, for imponderably mythic reasons, to slaughter his son, boil the body, and serve it up as soup to the gods. Aggrieved Olympians condemned him to an eternity of tantalization, food and drink forever just out of reach, and resolved to visit folly, blindness, and pride on his offspring forevermore. Family fortunes began a rapid decline, and by the time that Tantalus’ great-great-grandson Orestes reached adulthood, its history of rape, incest, cannibalism, and murder had generated a degree of domestic dysfunction that was pathological even by the standards of Greek mythology.

The play opens with news that Agamemnon, commander of the Greek armies and father of Orestes, has just triumphed at the Trojan Wars. But all is not well. Victory was purchased through the sacrifice of his own daughter, Iphigenia, and he has abducted Cassandra, the beautiful child of Troy’s King Priam, to have as his concubine. His wife, Clytemnestra, has meanwhile taken a lover of her own and sworn to avenge Iphigenia. When Agamemnon returns to the marital home, as oblivious to the obvious as every tragic protagonist should be, the tension mounts. Cassandra waits at the gates while he enters its portals—and the princess, cursed to know the future but powerless to change it, sees horror ahead. Hopping and screeching on the palace eaves are the Furies, supernatural guardians of cosmic propriety, and throbbing deep within are visions of anguish: torn wombs, a soil that streams blood, a bath swirling red . . . and Agamemnon, dead. “I know that odor,” intones Cassandra, as she steps up to the threshold. “I smell the open grave.” Screams engulf her, and the first act closes with Clytemnestra exulting over the bodies of her husband and his prize, a bloody knife in her right hand. Her work, she proclaims, is a masterpiece of justice.

It all leaves Orestes in a pickle. On the one hand, he loves his mother. On the other, he is honor-bound to slaughter her. Urged on by a crazed Chorus, he makes his way to the family palace, where he first cuts down her lover. He then forces Clytemnestra to gaze on the body. Pleading for her life, so desperate that she bares the breasts that once suckled him, she begs her son to accept that destiny played as much of a role in Agamemnon’s demise as her dagger. Orestes is torn between the claim of vengeance and the tie of affection, and the drama pivots on a moment of hesitation—before it tips. “This too,” retorts Orestes; “destiny is handing you your death.” He hurls his mother to the floor and makes her embrace her lover’s corpse before running her through with his sword. The sated Chorus regathers to pronounce that the family’s misfortunes have come to an end. Resolution remains an act away, however, and Orestes has of course won no more than his turn to bear the ancestral curse. As it settles, stifling, on his shoulders, he sees the serpent-haired Furies swarming to take revenge, and even the Chorus finally begins to waver. “Where will it end?” its members wail. “Where will it sink to sleep and rest, this murderous hate, this fury?”

Aeschylus’ answer comes in the final part of the trilogy. Shadowed by his mother’s supernatural avengers, Orestes seeks refuge at Apollo’s oracle at Delphi. Apollo, god of justice and healing, reassures him that he did the right thing, but advises him nevertheless to seek the protection of wise Pallas Athena. Orestes duly makes his way to her hilltop citadel on the Areopagus of Athens. The owl-eyed goddess is rather more equivocal. There are arguments both ways, she points out, and even she cannot resolve a conflict between right and right. Her solution is simple. She will summon ten Athenian citizens, bind them by oath, and make them decide.

The substance of the argument that ensues is less significant than its outcome—for although the jury splits evenly, Athena casts her vote for Orestes and is so impressed by her innovation that she prescribes its use in all future homicide cases. Athens, she pronounces, stands on the verge of unprecedented peace and tranquillity. Only the Furies remain unconvinced, hissing with repulsion at the thought of harmony, but even they are quieted by Athena’s assurance that they will have an honored place in her new court. Their venom has been drawn—and the snake-headed hags, optimistically renamed the Kindly Ones, close the play at the head of a torchlit procession through their blessed city.

Aeschylus intended his work as a celebration of Athens in particular and human potential in general. When it was first performed in 458 b.c., some two centuries after the scattered farms and fishing villages of the Attican peninsula had first begun to coalesce, the city was at its zenith. It had just seen off would-be invaders from Persia and transformed itself into a regional superpower, while political reforms were entrusting to its male citizens rights of participation and personal freedom never before seen in the ancient world. In a spirit epitomized by a famous assertion by a thinker called Protagoras that “man is the measure of all things,” its poets and philosophers were busily blazing trails that still dazzle more than two millennia later. Aeschylus’ brilliance manifested itself in a series of plays, and it was epitomized in the Oresteia. Whereas Homer had simply paid homage to Orestes as a righteous avenger, and Euripides would later resolve his anguish by having him acquitted before twelve gods, the playwright’s perspective was as radical as it was optimistic. Human honesty, he ventured, might be as sure a guide to the mysteries of justice as the most divine of oracles.

Straightforward though that message appears, it is easy to overrationalize it. Aeschylus’ faith was reflected by reality, in that legal reforms had just transferred the power to judge serious crimes from state officials to ordinary Athenian men, but the ritual that he revered was no fact-finding inquiry. There had been no uncertainty about what Orestes had done: he had deliberately murdered his mother, who had just done the same to his father. And just as the jurors were not convened to find facts, the defendant was not cleared because evidence proved his innocence: he was cleansed of guilt because they decided—by the barest of majorities, tipped by the casting vote of a goddess—that he was not blameworthy. Nor was vengeance removed from the process. Honoring the family by repaying wrongs done to it was still seen as part and parcel of the natural order, and any fifth-century Athenian would have regarded forgiveness as cowardly at best and accursed at worst. Aeschylus had made sure to give the Furies a dignified place in Pallas Athena’s court, and the clinching argument that the goddess used to secure their cooperation was a reminder that they had won the votes of half of the jurors. In his play, as in life, vengeance was being idealized and institutionalized, but it was certainly not being abolished.

Aeschylus’ stance reflected a tension between two ideas about justice that were always at odds with each other in the ancient world. One assumption, that people were at fault only if they had done evil deliberately, was almost as common in fifth-century Athens as it is today. However, there also existed another, more visceral belief—that some deeds demanded punishment regardless of the perpetrator’s intention, if the rage of the gods was to be forestalled. The view was notoriously prevalent among the ancient Hebrews, who enumerated an entire catalogue of unforgivable abominations, from sodomy to sex with mothers-in-law,* and used scapegoats and turtledoves to bear away the burden of countless lesser sins. In Greece itself, some three centuries before Aeschylus was born, the poems of a farmer called Hesiod had proposed that entire cities could suffer because of one man’s misdeeds. About three decades after the playwright died, Sophocles would retell the notorious tragedy of Oedipus Rex, whose unwitting seduction and slaughter of his mother and father, respectively, brought shame and pestilence onto his realm. And fifth-century Athenians did not just write about such matters; they regularly visited suffering on a minority to cleanse the majority. An annual festival called the Ostracism allowed Athenian men to banish a fellow citizen by vote, and although they often did so for practical reasons, the ritual was widely seen as a way of ridding the body politic of contamination. Athens, like other Greek cities, also maintained a stock of human scapegoats, known as the pharmakoi—comprising its poorest, lamest, and ugliest inhabitants—whose function was to be feasted and venerated at public expense, until famine or plague struck. They would then be dragged from their thrones and paraded about to the clatter of pans and the squeal of pipes, before being hounded out of the city gates under a hail of stones.

Trials themselves could operate to shift blame as well as discover it—as the Athenians also appreciated. Every midsummer up to the third century a.d., they held a festival known as the bouphonia, at which an axe-wielding official would, after sacrificing an ox, discard his weapon and flee the scene. Someone would then flay the beast, and all present would eat the meat, restitch the hide, stuff the carcass with straw, and yoke it to a plow—at which point a trial was convened to establish who, in the absence of the actual killer, was guilty of its death. Accusations were leveled first at the women who had brought the water to whet the blades. They would accuse the sharpeners. Those men, questioned in turn, would blame the people who had taken the axe and the knife from them to the slaughter. The messengers would accuse the carver, who laid one final charge: the true shame, he would argue, lay with his blade. And there the buck would stop. For when the knife damned itself by its silence, the axe was formally acquitted and the guilty weapon was hurled into the sea.

Although the modern mind tends to picture Greek courtrooms as sunbleached temples of debate and deliberation, a similar tension between reason and unreason characterized the rituals that were used to resolve actual crimes in fifth-century Athens. Freemen had gained the right to judge—which they would exercise not in groups of ten but in assemblies of up to a thousand and one—but while they were building a fizzing, babbling democracy, seventy silent percent of the adult population remained legal nonentities. Women were permitted to litigate only through guardians, while slaves could not even give evidence except under torture, on the strength of a theory that they were constitutionally incapable of telling the truth unless subjected to great pain.

Trials for homicide, a touchstone of the social order in any close-knit community, were not just affected by superstition but founded on it. It was commonly believed that killers exuded the miasma, a vapor so abhorrent to the gods that the slightest whiff could incite them to rage, so despicable that those around whom it clung were barred from temples, games, and the marketplace—and so persistent that only a trial could dispel it. The origins of the miasma are as misty as those of any myth, but its existence in fifth-century Athens was a firmly established sociological fact. Murder trials were held outdoors to minimize the risk of infection, and at least one defendant relied on its reality to prove his innocence, pointing out to his judges that he had recently sailed in a ship that had not sunk. Killers sometimes attended court to purge themselves even when there was no one to prosecute them—as might happen if the deceased was a legal cipher like a slave—and one Athenian tribunal, the prytaneion, was dedicated to nothing but the prosecution of killer beasts and murderous objects.* Defendants who had been exiled for one murder but wanted to cleanse themselves of a second charge were tried in the most prudent court of all. It convened at a stretch of Athenian shoreline called the Phreatto, where the accused addressed his judges from a boat which bobbed offshore at a suitably circumspect distance.

Media reviews

Advance praise for The Trial

“A vivid, colorful, anecdote-driven, witty, and intellectually provocative history of that most ubiquitous Western institution, the criminal trial. Anyone interested in the trial’s various current pop-cultural manifestations will find this book an edifying journey as well as a fun read.”

–Nadine Strossen, professor of law, New York Law School, president of the American Civil Liberties Union

“Amusing and colourful and anecdotal . . . a deeply thoughtful book of great contemporary relevance . . . Kadri’s panoramic and, yes, pragmatic viewpoint leaves the reader with moral and political insights that equip us to understand better our own disquieting times. That is a real achievement.”

–The Guardian (London)

“A timely book. Kadri makes it clear how long it has taken to arrive at this supposedly high point in judicial history, and consequently fires a warning shot at those who seek to erode hard-won legal traditions.”

–The Observer (London)

“Sadakat Kadri traces the development of the criminal trial through the ages . . . with verve, intelligence, humour, and clarity. . . . He tells good stories deftly managing to mix anecdote and serious analysis. An impressive performance.”

–The Times (London)

“This is a work of tremendous ambition: a panoramic review of law and justice told through powerful, individual stories. The book tackles dark themes, from the history of vengeance to the modern revival of torture, but navigates the horrors with glittering prose, sparkling wit, and boundless enthusiasm. At a time when politicians are discarding and exploiting legal traditions, it should be read by anyone interested in justice and the state of world.”

–Helena Kennedy, leading U.K. barrister