Summary

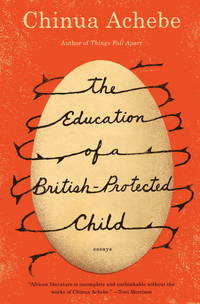

From the celebrated author of Things Fall Apart and winner of the Man Booker International Prize comes a new collection of autobiographical essays--his first new book in more than twenty years.Chinua Achebe's characteristically measured and nuanced voice is everywhere present in these seventeen beautifully written pieces. In a preface, he discusses his historic visit to his Nigerian homeland on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of Things Fall Apart, the story of his tragic car accident nearly twenty years ago, and the potent symbolism of President Obama's election. In "The Education of a British-Protected Child," Achebe gives us a vivid portrait of growing up in colonial Nigeria and inhabiting its "middle ground," recalling both his happy memories of reading novels in secondary school and the harsher truths of colonial rule. In "Spelling Our Proper Name," Achebe considers the African-American diaspora, meeting and reading Langston Hughes and James Baldwin, and learning what it means not to know "from whence he came." The complex politics and history of Africa figure in "What Is Nigeria to Me?," "Africa's Tarnished Name," and "Politics and Politicians of Language in African Literature." And Achebe's extraordinary family life comes into view in "My Dad and Me" and "My Daughters," where we observe the effect of Christian missionaries on his father and witness the culture shock of raising "brown" children in America.Charmingly personal, intellectually disciplined, and steadfastly wise, The Education of a British-Protected Child is an indispensable addition to the remarkable Achebe oeuvre.From the Hardcover edition.

From the publisher

Chinua Achebe lives in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. He was awarded the Man Booker International Prize in 2007.

From the Hardcover edition.

Details

-

Title

The Education of a British-Protected Child: Essays

-

Author

Chinua Achebe

-

Binding

Paperback

-

Pages

192

-

Volumes

1

-

Language

ENG

-

Publisher

Anchor Canada

-

Date

2010-10-05

-

ISBN

9780385667852 / 038566785X

-

Dewey Decimal Code

823.914

Excerpt

The Education of a British-Protected Child

The title I have chosen for these reflections may not be immediately clear to everybody and, although already rather long, may call for a little explanation or elaboration from me. But before I get to that, I want to deal with something which gives me even more urgent cause for worry—its content.

I hope my readers are not expecting to encounter the work of a scholar. I had to remind myself, when I was invited to give this address, that if they think you are a scholar, it must mean you are a scholar, of sorts. I say this "up front," as Americans would put it, to establish the truth quite early and quite clearly in case somehow a mistake has been made.

Though I would much rather have a successful performance than the satisfaction of being exonerated in failure, I cannot help adding that failure, sad as it would be, might also reveal the workings of poetic justice, because I missed the opportunity of becoming a clear-cut scholar forty years ago when Trinity College, Cambridge, turned down my application to study there after I took my first degree at the new University College, Ibadan. My teacher and sponsor from Ibadan had been a Cambridge man himself—one James Welch, about whom I shall say a few more words later. Anyhow, I stayed home then, and became a novelist. The only significant "if" of that personal history is that you, ladies and gentlemen, would be reading a scholarly essay today rather than an impressionistic story of a boy's growing up in British colonial Nigeria.

In its original form, this essay was delivered as the Ashby Lecture at Cambridge University, January 22, 1993. Eric Ashby, for whom the Ashby Lecture series is named, was master of Clare College at the university from 1959 to 1967. The lectures' broad theme is that of human values.

As you can see already, nothing has the capacity to sprout more readily or flourish more luxuriantly in the soil of colonial discourse than mutual recrimination. If I become a writer instead of a scholar, someone must take the rap. But even in such a rough house, masked ancestral spirits are respected and accorded immunity from abuse.

In 1957, three years after my failed Cambridge application, I had my first opportunity to travel out of Nigeria to study briefly at the BBC Staff School in London. For the first time I needed and obtained a passport, and saw myself defined therein as a "British Protected Person." Somehow the matter had never come up before! I had to wait three years more for Nigeria's independence in 1960 to end that rather arbitrary protection.

I hope nobody is dying to hear all over again the pros and cons of colonial rule. You would get only cons from me, anyway. So I want to indulge in a luxury which the contemporary culture of our world rarely allows: a view of events from neither the foreground nor the background, but the middle ground.

That middle ground is, of course, the least admired of the three. It lacks luster; it is undramatic, unspectacular. And yet my traditional Igbo culture, which at the hour of her defeat had ostensibly abandoned me in a basket of reeds in the waters of the Nile, but somehow kept anxious watch from concealment, ultimately insinuating herself into the service of Pharaoh's daughter to nurse me in the alien palace; yes, that very culture taught me a children's rhyme which celebrates the middle ground as most fortunate:

Obu-uzo anya na-afu mmo

Ono-na-etiti ololo nwa

Okpe-azu aka iko

The front one, whose eye encounters spirits

The middle one, the dandy child of fortune

The rear one of twisted fingers.

Why do the Igbo call the middle ground lucky? What does this place hold that makes it so desirable? Or, rather, what misfortune does it fence out? The answer is, I think, Fanaticism. The One Way, One Truth, One Life menace. The Terror that lives completely alone. So alone that the Igbo call it Ajo-ife-na-onu-oto: Bad Thing and Bare Neck. Imagine, if you can, this thing so alone, so singularly horrendous, that it does not even have the company of a necklace on its neck. The preference of the Igbo is thus not singularity but duality. Wherever Something Stands, Something Else Will Stand Beside It.

The middle ground is neither the origin of things nor the last things; it is aware of a future to head into and a past to fall back on; it is the home of doubt and indecision, of suspension of disbelief, of make-believe, of playfulness, of the unpredictable, of irony. Let me give you a thumbnail sketch of the Igbo people.

When the Igbo encounter human conflict, their first impulse is not to determine who is right but quickly to restore harmony. In my hometown, Ogidi, we have a saying, Ikpe Ogidi adi-ama ofu onye: The judgment of Ogidi does not go against one side. We are social managers rather than legal draftsmen. Our workplace is not a neat tabletop but a messy workshop. In a great compound, there are wise people as well as foolish ones, and nobody is scandalized by that.

The Igbo are not starry-eyed about the world. Their poetry does not celebrate romantic love. They have a proverb, which my wife detests, in which a woman is supposed to say that she does not insist that she be loved by her husband as long as he puts out yams for lunch every afternoon. What a drab outlook for the woman! But wait, how does the man fare? An old villager once told me (not in a proverb but from real life): "My favorite soup is egusi. So I order my wife never to give me egusi soup in this house. And so she makes egusi every evening!" This is then the picture: The woman forgoes love for lunch; the man tells a lie for his supper!

Marriage is tough; it is bigger than any man or woman. So the Igbo do not ask you to meet it head-on with a placard, nor do they ask you to turn around and run away. They ask you to find a way to cope. Cowardice? You don't know the Igbo.

Colonial rule was stronger than any marriage. The Igbo fought it in the battlefield and lost. They put every roadblock in its way and lost again. Sometimes I am asked by people who read novels as if novels were history books, what made the conversion of my people to Christianity in Things Fall Apart so easy.

Easy? I can tell you that it was not easy, neither in history nor in fiction. But a novel cannot replicate historical duration; it has to be greatly compressed. In actual fact, Christianity did not sweep through Igboland like wildfire. One illustration will suffice. The first missionaries came to the Niger River town of Onitsha in 1857. From that beachhead they finally reached my town, Ogidi, in 1892. Now, the distance from Onitsha to Ogidi is only seven miles. Seven miles in thirty-five years: that is, one mile every five years. That is no whirlwind.

I must keep my promise not to give a discourse on colonialism. But I will state simply my fundamental objection to colonial rule.

In my view, it is a gross crime for anyone to impose himself on another, to seize his land and his history, and then to compound this by making out that the victim is some kind of ward or minor requiring protection. It is too disingenuous. Even the aggressor seems to know this, which is why he will sometimes camouflage his brigandage with such brazen hypocrisy.

In the closing years of the nineteenth century, King Leo?pold II of the Belgians, whose activity in the Congo became a byword for colonial notoriety, was yet able to utter these words with a straight face:

I am pleased to think that our agents, nearly all of whom are volunteers drawn from the ranks of the Belgian Army, have always present in their minds a strong sense of the career in which they are engaged, and are animated with a pure feeling of patriotism; not sparing their own blood, they will the more spare the blood of the natives, who will see in them the all powerful protectors of their lives and their property, benevolent teachers of whom they have so great a need.1

It would be downright silly to suggest a parallel between British colonial rule in Nigeria and the scandalous activity of His Serene Majesty Leopold II in the Congo. And yet we cannot ignore the basic assumption of all European powers that participated in the Scramble for Africa. Just as all of Europe had contributed to the making of the dreadful character Mr. Kurtz, in Conrad's Heart of Darkness, so had all of Europe collaborated in creating the Africa that Kurtz would set out to deliver and that he would merely subject to obscene terror.

The grandiose words of King Leopold II may remind us that the colonizer was also wounded by the system he had created. He may not have lost land and freedom, like his colonized victim, but he paid a number of seemingly small prices, like the loss of a sense of the ridiculous, a sense of proportion, a sense of humor. Do you think Leopold II would have been capable of saying to himself: "Knock it off, chum; this is sheer humbug. You know the reason your agents are over there killing and maiming is that your treasury needs the revenue from rubber and ivory"? Admission of guilt does not necessarily absolve the offender, but it may at least shorten the recital and reliving of painful evidence.

From the Hardcover edition.

Media reviews

Praise for Chinua Achebe:

“Achebe is gloriously gifted with the magic of an ebullient, generous, great talent.”

— Nadine Gordimer, The New York Times Book Review

“What I know for sure is that I would not be the writer I am if it wasn’t for Chinua Achebe.”

— Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

“There is no way to be a writer — and not just an African writer, but a writer in the world, a serious writer — without responding to this book…. It has not only shaped the African imagination, but continues to shape the world imagination.”

— Chris Abani, author of Graceland, on Things Fall Apart

From the Hardcover edition.

About the author

Chinua Achebe lives in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. He was awarded the Man Booker International Prize in 2007.