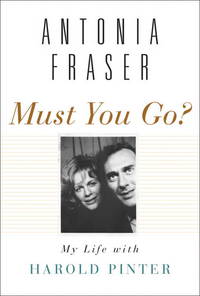

Must You Go?: My Life with Harold Pinter Hardback - 2010

by Antonia Fraser

From the publisher

ANTONIA FRASER is the author of many internationally bestselling historical works, including Love and Louis XIV, Marie Antoinette, which was made into a film by Sofia Coppola, The Wives of Henry VIII, Mary Queen of Scots, and Faith and Treason: the Gunpowder Plot. She has received the Wolfson Prize for History, the 2000 Norton Medlicott Medal of Britain's Historical Association, and the Franco-British Society's Enid McLeod Literary Prize.

Details

- Title Must You Go?: My Life with Harold Pinter

- Author Antonia Fraser

- Binding Hardback

- Edition Reprint

- Language EN

- Publisher Doubleday Canada, Toronto

- Date 2010-11-02

- ISBN 9780385668378

Excerpt

Chapter One

First Night

I first saw Harold across a crowded room, but it was lunchtime, not some enchanted evening, and we did not speak. I was having lunch in the Etoile restaurant in Charlotte Street; my companion pointed to a trio of men lunching opposite us. They were in fact Robert Shaw, Donald Pleasence and Harold; they were discussing Robert’s play, The Man in the Glass Booth, in which Harold would direct Donald. My companion admired Robert Shaw intensely: the handsome red-headed star who was said to do his own stuntwork and embodied machismo. Apparently I said thoughtfully: ‘I’ll take the dark one.’

On the next occasion I heard Harold’s voice, once aptly described by Arthur Miller as his ‘awesome baritone’, before we met. There was a recital about Mary Queen of Scots at the National Portrait Gallery, based on my book. Harold’s wife Vivien Merchant took the part of Mary, an actor took all the male parts and I read the narrative. These were professionals and I was intensely nervous; a kind friend in the audience told me afterwards that my knees were visibly shaking in my natty white trouser suit which had perhaps been the wrong call as a costume. Nevertheless things were running along smoothly – Vivien was an accomplished reader who gave Mary the correct Scottish accent – when suddenly there was some kind of interruption, a man’s voice raised, at the back of the gallery. Afterwards I enquired rather crossly what had happened. ‘Oh, that was Harold Pinter,’ I was told. ‘He attacked the attendant for opening the door in the middle of the recital.’ ‘I didn’t hear the door,’ I muttered, having just learned that the projected LP of the recital would have to be abandoned due to the disturbance. Later, when I was introduced to Harold, I asked him if it had indeed been him. `Yes,' he replied with satisfaction, `I do that kind of thing all the time.' In similar situations in the future, I sometimes reflected wryly: `I can't say I wasn't warned . . .'

And so to the evening of 8 January 1975 when I went to the first night of The Birthday Party at the Shaw Theatre, directed by Kevin Billington, husband of my sister Rachel. The author was of course there and there was to be a dinner party afterwards at the Billingtons' house in Holland Park.

At this point, Hugh and I, Harold and Vivien, had both been married, oddly enough, for exactly the same period almost to the day: that is, eighteen years since September 1956 when Harold and Vivien got married in a Registry Office in Bournemouth (they were in rep there) while I dolled myself up as Mary Queen of Scots and Hugh wore a kilt at the Catholic Church in WarwickStreet, Soho, with a full sung Nuptial Mass. Hugh and I had six children; Harold and Vivien had one. Hugh had been a Conservative MP since 1945; Vivien was a celebrated actress. I was forty-two; Harold was forty-four.

I considered myself to be happily married, or at any rate happy in my marriage; I admired Hugh for his cavalier nature, his high spirits, his courage - friends nicknamed him `Fearless Fraser' after some 1930s trapeze artist - his independence, his essential decency and kindness. I even admired him for his detachment, although his lackof emotional intimacy - he once told me that he preferred families to individuals - was with hindsight probably what doomed us. I on the other hand was intensely romantic and always had been since early childhood; the trouble with romantics is that they tend to gravitate towards other like-minded people, or people they choose to regard as such. So there had been romances. But I had never for one moment envisaged leaving my marriage.

Harold, I learned much later, did not consider himself to be happily married. He too had had his romances, perhaps more than the world, which cast him as the dark, brooding, eponymously `Pinteresque' playwright, realized. Later he also told me that he had never been in love before, but had once loved Vivien very much, her essential vulnerability inspiring him with a wish to protect her, before other matters drove them apart. They led essentially separate lives in an enormous stately six-storey house in Regent's ParkTerrace; but he too had never contemplated leaving his marriage.

8 January 1975

A very enjoyable dinner party at Rachel and Kevin's house in Addison Avenue: a long and convivial table. I was slightly disappointed not to sit next to the playwright who looked full of energy, with black curly hair and pointed ears, like a satyr. Gradually the guests filtered away. My neighbours Richard and Viv King offered me a lift up the road. `Wait a minute,' I said. `I must just say goodbye to Harold Pinter and tell him I enjoyed the play; I haven't said hello all evening.' They waited at the door. I went over to where Harold was sitting. `Wonderful play, marvellous acting, now I'm off.'

He looked at me with those amazing, extremely bright black eyes. `Must you go?' he said. I thought of home, my lift, taking the children to school the next morning, the exhausting past night in the sleeper from Scotland, my projected biography of King Charles II . . . `No, it's not absolutely essential,' I said.

About 2.30 in the morning, poor Rachel and Kevin were visibly exhausted, and we were the last guests. In the end, it was Harold who gave me a lift home, in a white car with a driver (he never drove at night having once been found `weaving' in Regent's Park). I offered him coffee. I actually gave him champagne. He stayed until six o'clock in the morning with extraordinary recklessness, but of course the real recklessness was mine.

We sometimes speculated later what would have happened if I had in fact answered: `Yes, I really must go.' Harold, convinced by then that I was his destiny, would gallantly reply: `I would have found you somehow.' But we had few friends in common: Edna O'Brien was one, and the producer Sam Spiegel another. But fundamentally we lived in different worlds. The night of 8/9 January was the chance and our chance.

Subsequently the tabloids made much of our different backgrounds, the working-class Jewish boy from the East End and the Catholic aristocrat with her title. But we were, in our early forties, a long way from our backgrounds and, as usual with the tabloids, these descriptions were more for headlines than accuracy. Although Harold was technically born into the working class - his father worked in a tailoring factory - ever since the success of The Caretaker in 1960 he had been extremely well-off by most standards: he was able, for example, to retire his father, worn-out with his labours, to salubrious Hove where his parents would live happily for another thirty years.

Again technically, since my father was an earl and my mother a countess, I could be argued to be an aristocrat. But my father, born Frank Pakenham, only succeeded to the Earldom of Longford when I was nearly thirty; my childhood was spent in a modest North Oxford house, my father, with no private income, teaching at the University. My mother, being a Harley Street doctor's daughter, was in any case convinced (and thus convinced us) that the middle classes were the salt of the earth whereas the aristocracy was feckless, unpunctual and extravagant, an assumption that our beloved father's attitude to life did nothing to discourage. I had no inherited money myself, and had earned my own living since the age of twenty-one, first working for a publisher and, after marriage, by journalism and books.

After the publication of Mary Queen of Scots, an unexpected bestseller in 1969, I found that for the first time in my life I had money to spend. Most of it went on the delightful taskof renovating Eilean Aigas, our house in the Highlands on an island in the River Beauly, which gave the impression of being untouched since the '45 rebellion. Our finances had been so perilous before this, since Hugh was entirely dependent on the then modest salary of an MP, that he had actually sold the house to a cousin by the previous Christmas - providentially the cousin's finances proved to be equally perilous and he reneged on the deal just in time for my windfall. To give only one example, I put in a heated open-air swimming pool round which the New Year celebrations regularly made the welkin ring. The truth was that by the mid 1970s, both in our different ways successful writers, Harold and I belonged to the same class: I will call it the Bohemian class.

13 January

While I was away, Harold had apparently called home on the public line; on Monday morning he called on my private line - I'm not sure how he got the number. We met for a drink at the Royal Lancaster Hotel in Bayswater (`an obscure place' he said truthfully) at 6 p.m. The bar was very darkand at first I couldn't see him. That made it all the more like a dream. But `so it wasn't all a dream' was the verdict of us both at the end. Told me of numerous obsessional phone calls – no answer - often from the famous Ladbroke Grove telephone box opposite Campden Hill Square. Had evidently told Kevin Billington about the whole thing! I began to guess this and he then admitted it. Can't say I care. `I am loopy about you: I feel eighteen' was the general theme; I said I preferred the word `dippy' . . .

The truth is that Harold has mesmerized me. Kept waking all night on the subject of a) him b) Benjie's departure for boarding school at Ampleforth. But a) has quite taken my mind off the horrible sadness of b). (Our third child and eldest son, aged not quite fourteen, was setting forth for his father's old school.)

23 January

Met Harold at 5.30 in the Royal Lancaster Hotel (he has telephoned daily). Parted at 11.30 to our respective matrimonial homes. We never left the bar, just talked and talked. Discussed among other things No Man's Land, his new play - to open at the National in April - and how he started to write it. At first he thought he was echoing himself (`What, two old men together again . . .'), then he thought: `You are what you are.' He had sent me the typescript after our first meeting. I liked the character of Spooner, the failed poet. So I asked him: `Did Spooner get the job?' On the whole he thought: No. `But Spooner is an optimist and there will be other jobs.' I said I would have to stop my ears at the first night for the darkof the ending: Winter/Night forever. But I liked `I'll drink to that' at the end. `That's the point,' Harold said, delighted . . . I am quite obsessed by him when I am with him. He tells me he is quite obsessed by me all the time - the days spent waiting to telephone, etc. . . . Described his life as a kind of prison, how, when can we meet, ever?

26 January

Taken to supper with Anthony Shaffer, author of Sleuth, by an old friend. The fashionable doctor for artists, Patrick Woodcock , warns me quite innocently against playwrights: `They're the worst.' Thought of Harold. I suppose I'm in love with him but there are many other things in my life. Yet: `oh, oh, the insomniac moonlight' in the words of the Scottish poet I like, Liz Lochhead.

30 January

Harold called. He asks: `Does it make you happy that we met? You wouldn't rather we hadn't met?'

1 February

I knew it would be a good day. Harold rang up in the morning and said, `Tea is on', having said two days ago `the situation is fluid'. Went at four, discreetly parking the car in Sussex Place. The house in Regent's ParkTerrace is vast, on first impression, and extremely sumptuous. I suppose it would not be so sumptuous if ten people lived in it. But with three, it is. A lot of large beautiful modern pictures in huge quiet rooms, apparently unlimited in number. Harold made tea. We went upstairs to the greeny-grey drawing room, vast pictures, few objects, greeny-grey light, enormous quantity of chairs and low sofas.

`I will show you my study presently.' And he did. At the top of the house, sixth floor in fact, we went up and up, like Tom Kitten. A marvellous room, much space, also less hushed. A deskwith windows overlooking Regent's Park and the other way, roofs. A chaise longue. A few chairs. Lots of books, novels and poetry. Harold presented me with his poems. `I would make a good secretary if you ever needed one,' I said, seeing the accommodation. He said: `the same thought had already crossed my mind.'

9 February

Joyous, dangerous and unavoidable - Harold's three words to Kevin Billington about us, quoted by Harold to me on the telephone. Not bad Pinteresque words.

19 February

Period of crisis. On Sunday Harold called to say that Vivien was very ill (pneumonia) in Hong Kong, with the dreadful possibility of not being able to go on and film Picnic at Hanging Rock in Australia - something she really wanted to do. He is racked with guilt. `Something of her own that I didn't write. That's what she wanted.' Much strain of cancellations and late-night calls. Nevertheless we met for drinks in the bar of the Churchill Hotel (twice).

21 February

Bought works about Harold at Foyles to feed my obsession. Seems to be in the class of Shakespeare judging by the nonsense that is talked . . . gave me a buzz all the same.

22 February

Harold in Hong Kong has written me two poems, one short, one very long, which he read to me twice: `I have spent the evening in my hotel room writing poems to you.' The long one began:

My heart is not a beat away from you

You turn, and touch the light of me.

You smile and I become the man

You loved before, but never knew

It ended:

You turn, and touch the light of me.

You smile, your eyes become my sweetest dream of you.

Oh sweetest love,

My heart is not a beat away from you.

This was the short one:

I know the place

It is true.

Everything we do

Connects the space

Between death and me,

And you.

It subsequently became a favourite poem of Harold's to mark this stage in our lives and he often recited it. However, when the poems arrived on the pale banana-coloured paper of the Peninsula Hotel, I protested about the comma after `me' which divided us and left him on the side of death and it was eliminated (although not put immediately after `death' as I wanted!).

22 February, cont.

He really seems mad with love. Diana Phipps, my confidante, on the telephone: `What happens when he asks you to pack your bags?' Me: `He won't. That's the great thing. He isn't a marryer. He has been married as long as I have.' Diana: `Don't count on it.'

In spite of that, thank God, she is wrong. Our relationship is more likely to bust out of passion because he won't be able to bear it, not at that level anyway. His love letters, leaving aside the poems, are extraordinary. From time to time he writes in his large, clear unmistakeable handwriting: `I'm calm. Calm.' and then he bursts out again, now with a big love letter, now with a poem - an extravagant poem, accompanied by a note: `This came out of the lonely middle of a desperate night thousands of miles from you, your image thudding in my skull. Don't be alarmed by it.'

24 February

Kevin Billington came round, thanks to Hong Kong calls ad infinitum, and we had an extremely intense conversation; beginning of course with much embarrassment as up to that point we were friendly but not close. `It's very serious for Harold,' he said and added: `I speak as Harold's friend and not because of our family relationship.' Me: `It's quite different for me . . . I haven't known anything like this before or perhaps once years ago but ever since I have tried to guard myself.' Kevin: `I'm very glad.'

25 February

Drink with Edna O'Brien at her request. She looked like a beautiful fortune-teller in her shawl by the fire, me her client. `He's much enraptured,' she said. Then: `I'm glad this is happening to him. Last summer when he was writing No Man's Land in that cottage I almost thought - well,' she hesitated. `He says he was waiting for death,' I replied.

28 February

The last call from Hong Kong. No more contact for the next week. But lots of poems have arrived on the banana-coloured hotel paper. I keep them in a clutch in my handbag and read and reread. One of them is the strongest love poem I have ever received.

Harold came back, with Vivien, on 10 March. He was in a terrible state when I didn't answer my telephone, also when I did. Explained later it was jet lag edging on panic that he had lost me.

11 March

Everything is now all right. But first I went to the Memorial Service for the murdered Ethiopian royal family who had helped me on my visit there in 1964. Deeply moving with the noble young Asfa Kassa, son of my patron Aserate Kassa, in charge: the grave and beautiful Crown Princess, a few other Ethiopians. I wept when Asfa read the lesson of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba in Amharic. (`And Solomon gave the Queen of Sheba all that she desired.')

Back here to wait for Harold. A knock. He was there. He clutched me and we clutched each other. At first it was almost desperate, he had suffered so much. Finally he said: `I feel like a new man' (as perhaps Solomon said to the Queen of Sheba).

12 March

Beautiful white and pink and green orchids from Harold with a note: `My heart.'

13 March

Day transformed at six when Harold rang up and said he wondered what my evening arrangements were. They had just finished testing leading ladies for the film of The Last Tycoon, produced by Sam Spiegel, for which Harold had written the screenplay: Harold read the Robert De Niro part. Met at the Stafford Hotel. We talked and talked. Harold back on the kick of saying he's going to tell Vivien sooner or later. `I should like to go away with you. Maybe Antarctica? But would you follow? I would like to be married to you when I'm eighty.' `I'll be seventy-eight.' Where is all this passion leading, I ask myself. The trouble is - when I am with him I don't care about anything and when I am not with him I don't care much either as I am always thinking about him.

14 March

Drink with Harold on his way from the National at the Strand Palace Hotel. Naturally he has told Peter Hall who was directing No Man's Land, `I've fallen in love', because of the need for an alibi.

16 March

Harold caused me a great deal of heart-beating terror by announcing he was going to tell Vivien: `I don't want to pretend I'm on a lecture tour.' I suppose I'm used to being on that lecture tour and it seems a perfectly good way of life. But Harold's force is burning me up and fascinating me all at the same time.

22/23 March

Weekend of considerable tension. Harold rang up Sunday evening and said he had told Vivien on Saturday: `I've met somebody.' Her rage at his dishonesty in deceiving her (for two and a half months). Vivien says about me: `She's a very bonny lady.' But - with whisky and nightfall more rage at the deception.

I did not know at this point that Vivien was on her way to being a serious alcoholic; a condition which would lead to her death in her early fifties. Nor did Harold discuss the subject with me at this point, either in extenuation of his own behaviour or out of guilt. There was the odd oblique reference which I did not understand.

24 March

In a way it is unfair for Vivien to pick on the deception as opposed to Harold's feelings, as he has always wanted to tell her; he couldn't before she went away and certainly couldn't when she was so ill. But nothing is fair in love (or war) whatever they say. For the first time I faced up to what another life would be like and whether it could ever exist. Or would be right. Right for whom? Never right for some. Diana Phipps: `Everyone must feel the temptation to leave their life behind. Don't forget that in fact no one ever does leave their life behind. You take it with you.'

In the meantime, as they say, I always wanted to be in love. Ever since I was a little girl. And I always wanted to know a genius, which I suppose Harold sort of is, but that did not lure me to him in the first place. I was lured, compelled by a superior force, something drawn out of me by him, which was simply irresistible.

27 March

Last day before Scotland for the school holidays. It is snowing and I went for a snowy walk in the park. Nevertheless there were wet heaps of grass to be seen where some incurable optimist had started to cut it. So, through the snow and blustering wind came the unmistakeable smell of summer: lawn mowings. Met Harold at the Royal Lancaster as once before. He gave me the first bound copy of No Man's Land with such a romantic inscription that I shall hardly be able to leave it about. The situation seems very fraught in the Pinter home and I honestly don't know how it will turn out. Mingled fright and excitement.

6 April

Horror has struck at the periphery of Harold's life. Mary Ure, wife of his buddy Robert Shaw, died the night after Robert had been out with Harold. Robert's guilt - and his own. In the end after a lot of talk and guilt, we both went round to see Robert Shaw hidden in the Savoy with his children. Harold in a fearful state. The Shaw daughters full of fortitude. His son, the image of Mary, infinitely touching.

The rest of April passed with me toing and froing between London and Scotland during the school holidays, while being extremely active in campaigning for Public Lending Right (I was Chairman of the Society of Authors). Vivien left Hanover Terrace for a while; Harold continued to attend rehearsals of No Man's Land.

14 April

Harold came to lunch before rehearsal. Now very gloomy about the play - just because Sir Ralph Richardson can't happen to get the words in the right order. This is torture for him. But says he is a little bit in love with Ralph all the same. Me: `As he is a man and seventy-two, that's okay.' Harold and Sir Ralph: the perfect actor for him except for this one fault which could utterly ruin everything Harold conceives the play to be, in terms of rhythm and poetry.

20 April - Sunday morning

Hugh asked: `Are you in love with someone else?' I don't think he expected to get the answer `Yes! I am madly in love with someone else.' After a bit I told him who it was. Hugh, grimly: `The best living playwright. Very suitable.' Then: `How old is he?' Me: `My age.' Hugh: Well, that's also very suitable.' I had dreaded this moment so much, thought it would never come, because it never could come. Then it did come, suddenly, in a twinkling of an eye, and in a way it was perfectly all right. Except as Harold pointed out about his own situation, nothing is ever the same again.

The next weeks were agonizing for all concerned with a few bright moments which did not relate to personal relationships.

23 April

The great Public Lending Right Demo Day in Belgrave Square outside the Ministry. Wore spring-like suit to LBC Radio at 8.30 a.m.; frozen by 11.30. We hustled importantly on to a traffic island in Belgrave Square, media actually outnumbering the authors. But Angus Wilson came all the way up from Suffolk, good sweet man that he is. Bridget Brophy magnificent and large in a white princess-line dress, Maureen Duffy in a mauve frilly shirt with her trouser suit, running the show with her loud hailer. Gave interviews to TV, having been told by Frank Muir not to smile: `Look grim and defiant.' Natasha (my fourth child: the others were Rebecca, Flora, Benjie, Damian and Orlando) said: `You looked like someone who wanted to have her own way. Like a queen, but cross,' she added kindly.

Met Harold for lunch and gave him my lucky agate to hold in his sweaty palm at the first night of No Man's Land. Went with Rachel and Kevin, and my brother Thomas to the theatre. Drink in the upstairs bar. Suddenly Harold walked in. Transfixed. Both of us. Could hardly speak or look at him. `Hello, Antonia,' and hand outstretched: a very deep gravelly voice.

Then the play . . . In the interval Milton Shulman, there as drama critic of the Evening Standard , asked innocently: `What's it all about?' Revealed that he had been asleep in the first half. Critics!!! Me: `It's about the creative artist locked in his own world. Gielgud as Spooner is shabby reality trying to get in.' Milton: ??? Me: `Well, I'm only trying to help.' Later we four went to Odin's. Harold telephoned me from the first-night party at Peter Hall's flat in the Barbican. Harold: `I was happy with it.' He went on: `I watched you when you walked across the front of the stalls going to your seat after the interval. I liked your dress. You looked so beautiful.' (I still have the dress.) Me: `I just couldn't speak in the bar.'

24 April

Vivien told Harold: `The myth of the happy Pinter marriage is exploded. It hasn't really existed for many years.' She had not come to the first night; Harold took his son. This morning the Daily Mail blew the gaff, talking of `a literary friendship'. So that's what they call it these days!

25 April

Harold is leaving Vivien for Sam Spiegel's flat in Grosvenor House `So that murder shall not take place.' It's difficult to comment on this because up till the other night I had thought their marriage a happy one (albeit not perfect . . . because perfect marriages if they exist are immune from late-night romantic encounters). So I don't understand anything at the moment.

28 April

Harold moved into Sam's flat. Tried to liken it to a ship: large for a ship. Actually quite large for a flat. But the point is really, the grimness of anyone leaving their home where everything is arranged to their satisfaction, to live in a place where it isn't. Harold very low. The prospect of Paris seems to cheer. But I'm sure the missing of home remains an eternal thing.

5 - 15 May

In Paris at the Hotel Lancaster. What can I write? (I'm back in London.) However, here goes. We had our suite, Harold's famous emphasis on suites! A sitting room, tres charmant, a large bedroom and another one for me, I insisted on that for telephonic reasons. Harold met me at Charles de Gaulle Airport, I floated up in the new moving passageway as in a dream towards him. Chauffeur-driven car (another great obsession). Thereafter we lived in our suite and went to restaurants and never really did anything at all for ten days. Very restful that, doing nothing. We did take very small walks in the truly wet and freezing weather (I bought two umbrellas when I was in Paris) ending fairly rapidly in bars. Like Hirst in No Man's Land, Harold drinks a hell of an amount. Mostly we talked, sometimes good talks, sometimes `a good talk' about the future. Occasionally Harold whirled into jealousy about the past.

We met Barbara Bray, the translator and literary critic with whom Harold had worked on the Proust screenplay for so long, Beckett's girlfriend. Despite avowed Women's Lib feelings, Barbara maddened Harold by looking and talking all the time to him, never me. I didn't notice so wasn't maddened. Finally she said: `I should be interested in you as a writer because you're a woman, but of course it's Harold I'm interested in.' `So that's two of us,' I said. Much more fun was the ravishing Delphine Seyrig who failed to turn up as a cool blonde as I had hoped (see The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie), but emerged as a frizzy red-haired biker holding a helmet. She was nevertheless delightful, very warm to me, and her beauty could not be quenched.

On Sunday evening Harold said we were swimming nearer and nearer the sea, in a series of rock pools. The ocean was ahead. Someone I adored was Harold's translator Eric Kahane: a kindred spirit. (We became lifelong friends.) Once back, Harold went to Sam's flat at Grosvenor House, me to Campden Hill Square. But Harold found a lawyer's letter from Withers & Co. informing him that his wife was suing him for divorce, the cause being his own admitted adultery with me. This was the one thing we were sure would never happen, even though Vivien had written to Paris to announce what she would do if he didn't return. Harold to me: `Tell your husband that my intentions are strictly honourable.'

16 & 17 May

Harold in a terrible state about money although he seems to me to earn a fortune, enough anyway not to worry. I think worrying about money is a substitute for worrying about the future. Harold has written me a magic poem called `Paris': it ends `She dances in my life.' I cling to that. What will happen next?

Paris

The curtain white in folds,

She walks two steps and turns,

The curtain still, the light

Staggers in her eyes.

The lamps are golden.

Afternoon leans, silently.

She dances in my life.

The white day burns.

Media reviews

Praise for Must You Go?:

"Moving and compellingly readable. . . . Written with palpable love, warmth, affection and a huge sense of loss. . . . A heart-warming love story."

— The Telegraph

"Few people have the emotional capacity for a grand passion, or the talent for expressing it, as she does. Lady Antonia is a narrative historian and she has spent the year since Pinter died writing out their love story."

— Daily Mail

About the author

More Copies for Sale

Must You Go? : My Life with Harold Pinter

by Fraser, Antonia

- Used

- Condition

- Used - Very Good

- ISBN 13

- 9780385668378

- ISBN 10

- 0385668376

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Seller

-

Mishawaka, Indiana, United States

- Item Price

-

$5.00FREE shipping to USA

Show Details

Must You Go?

by Fraser, Antonia

- Used

- Condition

- Used - Very Good

- ISBN 13

- 9780385668378

- ISBN 10

- 0385668376

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Seller

-

Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

- Item Price

-

$9.99$14.99 shipping to USA

Show Details

Must You Go?

by Fraser, Antonia

- Used

- Condition

- Used - Good

- ISBN 13

- 9780385668378

- ISBN 10

- 0385668376

- Quantity Available

- 2

- Seller

-

Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

- Item Price

-

$9.99$14.99 shipping to USA

Show Details

Must You Go?

by Fraser, Antonia

- Used

- Condition

- Used - Good

- ISBN 13

- 9780385668378

- ISBN 10

- 0385668376

- Quantity Available

- 2

- Seller

-

Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

- Item Price

-

$9.99$14.99 shipping to USA

Show Details

Must You Go?: My Life with Harold Pinter

by Antonia Fraser,

- Used

- Hardcover

- first

- Condition

- Used - Fine in Fine dust jacket

- Edition

- First Canadian Edition; First Printing

- Binding

- Hardcover

- ISBN 13

- 9780385668378

- ISBN 10

- 0385668376

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Seller

-

Amherst, Nova Scotia, Canada

- Item Price

-

$20.00$9.50 shipping to USA

Show Details

Remote Content Loading...

Hang on… we’re fetching the requested page.

Book Conditions Explained

Biblio’s Book Conditions

-

As NewThe book is pristine and free of any defects, in the same condition as when it was first newly published.

-

Fine (F)A book in fine condition exhibits no flaws. A fine condition book closely approaches As New condition, but may lack the crispness of an uncirculated, unopened volume.

-

Near Fine (NrFine or NF)Almost perfect, but not quite fine. Any defect outside of shelf-wear should be noted.

-

Very Good (VG)A used book that does show some small signs of wear - but no tears - on either binding or paper. Very good items should not have writing or highlighting.

-

Good (G or Gd.)The average used and worn book that has all pages or leaves present. ‘Good’ items often include writing and highlighting and may be ex-library. Any defects should be noted. The oft-repeated aphorism in the book collecting world is “good isn’t very good.”

-

FairIt is best to assume that a “fair” book is in rough shape but still readable.

-

Poor (P)A book with significant wear and faults. A poor condition book can still make a good reading copy but is generally not collectible unless the item is very scarce. Any missing pages must be specifically noted.