Description:

Doubleday Religious Publishing Group, The, 2004. Hardcover. Good. Disclaimer:Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less.Dust jacket quality is not guaranteed.

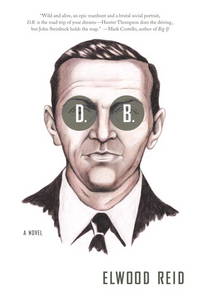

d.b by reid, elwood

by reid, elwood

Similar copies are shown below.

Similar copies are shown to the right.

Stock Photo: Cover May Be Different

d.b

by reid, elwood

- Used

- Hardcover

- first

Hard Cover. Doubleday 2004. Very Good Condition, This Copy. DJ Same. First Edition. Unless Listed in this decription, VG or Better.

-

Bookseller

Independent bookstores

(US)

- Format/Binding Hard Cover

- Book Condition Used

- Binding Hardcover

- ISBN 10 0385497385

- ISBN 13 9780385497381

We have 11 copies available starting at $6.35.

D. B.

by Elwood Reid

- Used

- good

- Hardcover

- Condition

- Used - Good

- Binding

- Hardcover

- ISBN 10 / ISBN 13

- 9780385497381 / 0385497385

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Seller

-

Seattle, Washington, United States

- Item Price

-

$6.35FREE shipping to

Show Details

Item Price

$6.35

FREE shipping to

Stock Photo: Cover May Be Different

D.B.: A

by D.B.: A Novel Novel

- Used

- Condition

- Used - Very Good

- ISBN 10 / ISBN 13

- 9780385497381 / 0385497385

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Seller

-

Hanover Park, Illinois, United States

- Item Price

-

$1.99$4.50 shipping to

Show Details

Description:

Used - Very Good. Great condition for a used book?minimal wear. Great condition for a used book?minimal wear.

Item Price

$1.99

$4.50

shipping to

Stock Photo: Cover May Be Different

D. B

by Reid, Elwood

- Used

- Condition

- Used - Good

- ISBN 10 / ISBN 13

- 9780385497381 / 0385497385

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Seller

-

Mishawaka, Indiana, United States

- Item Price

-

$6.88FREE shipping to

Show Details

Description:

Doubleday Religious Publishing Group, The. Used - Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages.

Item Price

$6.88

FREE shipping to

Stock Photo: Cover May Be Different

D.B

by Elwood Reid

- Used

- good

- Hardcover

- Condition

- Used - Good

- Binding

- Hardcover

- ISBN 10 / ISBN 13

- 9780385497381 / 0385497385

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Seller

-

HOUSTON, Texas, United States

- Item Price

-

$7.79FREE shipping to

Show Details

Description:

Doubleday, 2004-07-13. Hardcover. Good.

Item Price

$7.79

FREE shipping to

Stock Photo: Cover May Be Different

D. B. - Advanced Reading Copy

by Reid, Elwood

- Used

- very good

- Paperback

- first

- Condition

- Used - Very Good

- Edition

- First Edition

- Binding

- Paperback

- ISBN 10 / ISBN 13

- 9780385497381 / 0385497385

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Seller

-

Spokane Valley, Washington, United States

- Item Price

-

$5.75$4.95 shipping to

Show Details

Description:

Doubleday & Company, Inc., 2004. Trade Paperback - VG - Book is clean and tight with light wear - ARC - First Edition - 356 pages.. First Edition. Trade Paperback. Very Good. Advanced Reading Copy (ARC).

Item Price

$5.75

$4.95

shipping to

Stock Photo: Cover May Be Different

D. B. - Advanced Reading Copy

by Reid, Elwood

- Used

- very good

- Paperback

- first

- Condition

- Used - Very Good

- Edition

- First Edition

- Binding

- Paperback

- ISBN 10 / ISBN 13

- 9780385497381 / 0385497385

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Seller

-

Spokane Valley, Washington, United States

- Item Price

-

$5.75$4.95 shipping to

Show Details

Description:

Doubleday & Company, Inc., 2004. Trade Paperback - VG - Book is clean and tight with light wear - ARC - First Edition - 356 pages.. First Edition. Trade Paperback. Very Good. Advanced Reading Copy (ARC).

Item Price

$5.75

$4.95

shipping to

Stock Photo: Cover May Be Different

D.B.: A Novel

by Reid, Elwood

- Used

- Hardcover

- Condition

- Used - Very Good

- Binding

- Hardcover

- ISBN 10 / ISBN 13

- 9780385497381 / 0385497385

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Seller

-

Chicago, Illinois, United States

- Item Price

-

$7.25$3.50 shipping to

Show Details

Description:

Doubleday. Used - Very Good. 2004. Hardcover. Very Good.

Item Price

$7.25

$3.50

shipping to

Stock Photo: Cover May Be Different

D.B

by Elwood Reid

- Used

- Hardcover

- Condition

- Used:Good

- Binding

- Hardcover

- ISBN 10 / ISBN 13

- 9780385497381 / 0385497385

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Seller

-

HOUSTON, Texas, United States

- Item Price

-

$12.84FREE shipping to

Show Details

Description:

Doubleday, 2004-07-13. Hardcover. Used:Good.

Item Price

$12.84

FREE shipping to

Stock Photo: Cover May Be Different

D. B. (Advanced Reading Copy/ARC)

by Reid, Elwood

- Used

- very good

- Paperback

- first

- Condition

- Used - Very Good

- Edition

- First Edition

- Binding

- Paperback

- ISBN 10 / ISBN 13

- 9780385497381 / 0385497385

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Seller

-

Spokane Valley, Washington, United States

- Item Price

-

$11.50$4.95 shipping to

Show Details

Description:

Doubleday, 2004. Trade Paperback - VG - Book is clean and tight with light wear - ARC - 356 pages.. First Edition. Trade Paperback. Very Good. Advanced Reading Copy (ARC).

Item Price

$11.50

$4.95

shipping to

D.B.

by Reid, Elwood

- Used

- Fine

- Hardcover

- first

- Condition

- Used - Fine

- Jacket Condition

- Near Fine

- Edition

- First Edition

- Binding

- Hardcover

- ISBN 10 / ISBN 13

- 9780385497381 / 0385497385

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Seller

-

Monroe, Michigan, United States

- Item Price

-

$17.95$5.00 shipping to

Show Details

Description:

New York, NY, USA: Doubleday, 2004 unused book from closed bookstore inventory; clean and tight and square, inside is clean and unmarked; DJ has no chips, creases or tears, edges are slightly bumped, cover very slightly rubbed from normal shelf wear

Item Price

$17.95

$5.00

shipping to