Theobold's Shakespeare. Volumes 1, 2 & 3.

by William Shakespeare

- Used

- good

- Hardcover

- first

- Condition

- Good

- Seller

-

Scarborough , North Yorkshire, United Kingdom

Payment Methods Accepted

About This Item

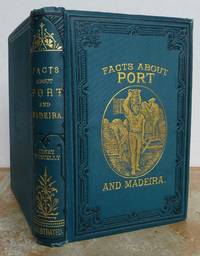

Leather binding with gilt title and decoration on the spine.

The first three volumes of Theobald's great work Theobald's fame and contribution to English letters rests with his 1726 Shakespeare Restored, or a Specimen of the many Errors as well Committed as Unamended by Mr Pope in his late edition of this poet; designed not only to correct the said Edition, but to restore the true Reading of Shakespeare in all the Editions ever published. Theobald's 1733 Shakespeare edition was far the best produced before 1750, and it has been the cornerstone of all subsequent editions. Theobald not only corrected variants but chose among best texts and undid many of the changes to the text that had been made by earlier 18th century editors. Edmond Malone's later edition (the standard from which modern editor's act) was built on Theobald's.

Lewis Theobald (baptised 2 April 1688 – 18 September 1744), British textual editor and author, was a landmark figure both in the history of Shakespearean editing and in literary satire. He was vital for the establishment of fair texts for Shakespeare, and he was the first avatar of Dulness in Alexander Pope's The Dunciad. Lewis Theobald was the son of Peter Theobald, an attorney, and his second wife, Mary. He was born in Sittingbourne, Kent, and baptized there on 2 April 1688. When Peter Theobald died in 1690, Lewis was taken into the Rockingham household and educated with the sons of the family, which gave him the grounding in Greek and Latin that would serve his scholarship throughout his career. As a young man, he was apprenticed to an attorney and then set up his own law practice in London. In 1707, possibly while he was apprenticing, he published A Pindaric Ode on the Union of Scotland and England and Naufragium Britannicum. In 1708 his tragedy The Persian Princess was performed at Drury Lane. Theobald translated Plato's Phaedo in 1714 and was contracted by Bernard Lintot to translate the seven tragedies of Aeschylus but didn't deliver. He translated Sophocles's Electra, Ajax, and Oedipus Rex in 1715. Theobald also wrote for the Tory Mist's Journal. He attempted to make a living with drama and began to work with John Rich at Drury Lane, writing pantomimes for him including Harlequin Sorcerer (1725), Apollo and Daphne (1726), The Rape of Proserpine (1727), and Perseus and Andromeda (1730); many of these had music by Johann Ernst Galliard. He also probably plagiarized a man named Henry Meystayer. Meystayer had given Theobald a draft of a play called The Perfidious Brother to review, and Theobald had it produced as his own work. Theobald's fame and contribution to English letters rests with his 1726 Shakespeare Restored, or a Specimen of the many Errors as well Committed as Unamended by Mr Pope in his late edition of this poet; designed not only to correct the said Edition, but to restore the true Reading of Shakespeare in all the Editions ever published. Theobald's variorum is, as its subtitle says, a reaction to Alexander Pope's edition of Shakespeare. Pope had "smoothed" Shakespeare's lines, and, most particularly, Pope had, indeed, missed many textual errors. In fact, when Pope produced a second edition of his Shakespeare in 1728, he incorporated many of Theobald's textual readings. Pope claimed that he took in only "about twenty-five words" of Theobald's corrections, but, in truth, he took in most of them. Additionally, Pope claimed that Theobald hid his information from Pope. Pope was as much a better poet than Theobald as Theobald was a better editor than Pope, and the events surrounding Theobald's attack and Pope's counterattack show both men at their heights. Theobald's Shakespeare Restored is a judicious, if ill-tempered, answer to Pope's edition, but in 1733 Theobald produced a rival edition of Shakespeare in seven volumes for Jacob Tonson, the book seller. For the edition, Theobald worked with Bishop Warburton, who later also published an edition of Shakespeare. Theobald's 1733 edition was far the best produced before 1750, and it has been the cornerstone of all subsequent editions. Theobald not only corrected variants but chose among best texts and undid many of the changes to the text that had been made by earlier 18th century editors. Edmond Malone's later edition (the standard from which modern editor's act) was built on Theobald's. Theobald (pronounced by Pope as "Tibbald," though living members of his branch of the Theobald family say it was pronounced as spelled then, as it is today) was rewarded for his public rebuke of Pope by becoming the first hero of Pope's The Dunciad in 1728. In the Dunciad Variorum, Pope goes much farther. In the apparatus to the poem, he collects ill comments made on Theobald by others, gives evidence that Theobald wrote letters to Mist's Journal praising himself, and argues that Theobald had meant his Shakespeare Restored as an ambush. One of the damning bits of evidence came from John Dennis, who wrote of Theobald's Ovid: "There is a notorious Ideot . . . who from an under-spur-leather to the Law, is become an under-strapper to the Play-house, who has lately burlesqu'd the Metamorphoses of Ovid by a vile Translation" (Remarks on Pope's Homer p. 90). Until the second version of The Dunciad in 1741, Theobald remained the chief of the "Dunces" who led the way toward night (see the translatio stultitia) by debasing public taste and bringing "Smithfield muses to the ears of kings." Pope attacks Theobald's plagiarism and work in vulgar drama directly, but the reason for the fury was in all likelihood the Shakespeare Restored. Even though Theobald's work is invaluable, Pope succeeded in so utterly obliterating the character of the man that he is known by those who do not work with Shakespeare only as a dunce, as a dusty, pedantic, and dull-witted scribe. In this, "The Dunciad" affected Theobald's reputation for posterity much as Dryden's "Mac Flecknoe" affected Thomas Shadwell's. In 1727, Theobald produced a play Double Falshood; or The Distrest Lovers, which he claimed to have based on a lost play by Shakespeare. Pope attacked it as a fraud but admitted in private that he believed Theobald to have worked from, at the least, a genuine period work. Modern scholarship continues to be divided on the question of whether Theobald was truthful in his claim. Double Falshood may be based on the lost Cardenio, by Shakespeare and John Fletcher, which Theobald may have had access to in a surviving manuscript, which he revised for the tastes of the early eighteenth century. However, Theobald's claims about the origins of the play are not consistent and have not been uniformly accepted by critics. The History of Cardenio, often referred to as merely Cardenio, is a lost play, known to have been performed by the King's Men, a London theatre company, in 1613. The play is attributed to William Shakespeare and John Fletcher in a Stationers' Register entry of 1653. The content of the play is not known, but it was likely to have been based on an episode in Miguel de Cervantes's Don Quixote involving the character Cardenio, a young man who has been driven mad and lives in the Sierra Morena. Thomas Shelton's translation of the First Part of Don Quixote was published in 1612, and would thus have been available to the presumed authors of the play. Two existing plays have been put forward as being related to the lost play. A song, "Woods, Rocks and Mountains", set to music by Robert Johnson, has also been linked to it. Although there are records of the play having been performed, there is no information about its authorship earlier than a 1653 entry in the Stationers' Register. The entry was made by Humphrey Moseley, a bookseller and publisher, who was thereby asserting his right to publish the work. Moseley is not necessarily to be trusted on the question of authorship, as he is known to have falsely used Shakespeare's name in other such entries. It may be that he was using Shakespeare's name to increase interest in the play. However, some modern scholarship accepts Moseley's attribution, placing the lost work in the same category of collaboration between Fletcher and Shakespeare as The Two Noble Kinsmen. Fletcher based several of his later plays on works by Cervantes, so his involvement is plausible.

A possible synopsis of Cardenio After a few adventures together, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza discover a bag full of gold coins along with some papers, which include a sonnet describing the poet's romantic troubles. Quixote and Sancho search for the person to whom the gold and the papers belong. They identify the owner as Cardenio, a madman living in the mountains. Cardenio begins to tell his story to Quixote and Sancho: Cardenio had been deeply in love with Luscinda, but her father refused to let the two marry. Cardenio had then been called to service by Duke Ricardo, and befriended the duke's son, Don Fernando. Fernando had coerced a young woman named Dorotea into agreeing to marry him, but when he met Luscinda, he decided to steal her from Cardenio. At this point in Cardenio's narration, however, Quixote interrupts, prompting Cardenio to leave in a fit of violent madness. Quixote, inspired by Cardenio, decides to imitate the madness of various chivalric knights, and so sends Sancho away. Coming to an inn, Sancho encounters a barber and a priest, who have been following Quixote with intentions to bring him back home. Following Sancho into the mountains, the barber and priest encounter Cardenio for themselves. Cardenio, back to his wits, relates his complete story to them: after sending Cardenio away on an errand, Fernando convinced Luscinda's father to let him marry Luscinda instead. Luscinda then wrote to Cardenio, telling him of the planned wedding, and of her intentions to commit suicide rather than marry Fernando. Cardenio arrived at the wedding and, hidden, saw Luscinda agree to the exchange of vows, then promptly faint. Feeling betrayed, Cardenio left for the mountains. After concluding his story, Cardenio and the two other men stumble upon a woman, who is revealed as being Dorotea. Having been scorned by Fernando, she had travelled to confront him, only to learn the events of the wedding, including the discovery of a dagger on Luscinda's person after her fainting, and how she later ran away to flee Fernando and find Cardenio. Dorotea had then been driven into the mountains after her accompanying servant tried to force himself on her. Reinvigorated by their meeting, Cardenio and Dorotea resolve to help each other regain their respective lovers. After helping the barber, the priest, and Sancho lure Quixote out of the mountains, Cardenio and Dorotea return to the inn with the others. At the inn, Cardenio and Dorotea find themselves suddenly reunited with Fernando and Luscinda. Cardenio and Luscinda redeclare their love for each other, while Fernando repents and apologizes to them all.

Double Falsehood (archaic spelling: Double Falshood) or The Distrest Lovers is a 1727 play by the English writer and playwright Lewis Theobald, although the authorship has been contested ever since the play was first published, with some scholars considering that it may have been written by John Fletcher and William Shakespeare. Some authors believe that it may be an adaptation of a lost play by Shakespeare and Fletcher known as Cardenio. Theobald himself claimed his version was based on three manuscripts of an unnamed lost play by Shakespeare. The 1727 play is based on the "Cardenio" episode in Miguel de Cervantes's Don Quixote, which occurs in the first part of the novel. The author of the play appears to know the novel through Thomas Shelton's English translation, which appeared in 1612. Theobald's play changes the names of the main characters from the Spanish original: Cervantes' Cardenio becomes Julio, his Lucinda becomes Leonora; Don Fernando is turned into Henriquez, and Dorothea into Violante. Publisher Humphrey Moseley was the first to link Cardenio with Shakespeare: the title page of his edition of 1647, entered at the Stationers' Register on 9 September 1653, credits the work to "Mr Fletcher & Shakespeare". In all, Moseley added Shakespeare's name to six plays by other writers, attributions which have always been received with scepticism. Theobald's claim of a Shakespearean foundation for his Double Falshood met with suspicion, and even accusations of forgery, from contemporaries such as Alexander Pope, and from subsequent generations of critics as well. Nonetheless Theobald is regarded by critics as a far more serious scholar than Pope, and as a man who "more or less invented modern textual criticism". The evidence of Shakespeare's connection with a dramatization of the Cardenio story comes from the entry in the Stationers' Register, but Theobald could not have known of this evidence, "since it was not found until long after his death". There appears to be agreement among scholars that the 18th century Double Falsehood is not a forgery, but is based on the lost Cardenio of 1612–13, and that the original authors of Cardenio were John Fletcher and possibly William Shakespeare. In March 2010, The Arden Shakespeare published Double Falsehood, with a "Note on this Edition" stating that the edition "makes its own cautious case for Shakespeare's participation in the genesis of the play," followed with speculations regarding how such a case might, in an imagined future, either be "substantiated beyond all doubt" or "altogether disproved". Arden editor, Brean Hammond, in the introduction, states that recent analysis based on linguistics and style "lends support" to the idea that Shakespeare and Fletcher's hand can be detected in the 18th Century edition. Hammond then expresses the hope that his edition "reinforces the accumulating consensus that the lost play has a continuing presence in its eighteenth-century great-grandchild.' Author and critic Kate Maltby cautions against promoting Double Falsehood with exaggerated statements. She points out that nowhere does the Arden editor of Double Falsehood make the "grandiose claim" found on advertisements for a production of the play that invite people to come and 'Discover a Lost Shakespeare'. She points out that if a young person sees a production of Double Falsehood, and is told it is by Shakespeare, they may come away with the "lifelong conviction that 'Shakespeare' is pallid and dull." In 2015, Ryan L. Boyd and James W. Pennebaker of the University of Texas at Austin published research in the journal Psychological Science that reported statistical and psychological evidence suggesting Shakespeare and Fletcher may have co-authored Double Falsehood, with Theobald's contribution being "very minor". By aggregating dozens of psychological features of each playwright derived from validated linguistic cues, the researchers found that they were able to create a "psychological signature" (i.e., a high-dimensional psychological composite) for each authorial candidate. These psychological signatures were then mathematically compared with the psycholinguistic profile of Double Falsehood. This allowed the researchers to determine the probability of authorship for Shakespeare, Fletcher, and Theobald. Their results challenge the suggestion that the play was a mere forgery by Theobald. Additionally, these results provided strong evidence that Shakespeare was the most likely author of the first three acts of Double Falsehood, while Fletcher likely made key contributions to the final two acts of the play. The play was first produced on 13 December 1727 at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, and published in 1728. The drama was revived at Covent Garden on 24 April 1749, and performed again on 6 May that year. Later performances occurred in 1781 and 1793, and perhaps in 1770 also. After the first edition of 1728, later editions appeared in 1740 and 1767.

Edmond Malone (4 October 1741 – 25 May 1812) was an Irish Shakespearean scholar and editor of the works of William Shakespeare. Assured of an income after the death of his father in 1774, Malone was able to give up his law practice for at first political and then more congenial literary pursuits. He went to London, where he frequented literary and artistic circles. He regularly visited Samuel Johnson and was of great assistance to James Boswell in revising and proofreading his Life, four of the later editions of which he annotated. He was friendly with Sir Joshua Reynolds and sat for a portrait now in the National Portrait Gallery. He was one of Reynolds' executors and published a posthumous collection of his works (1798) with a memoir. Horace Walpole, Edmund Burke, George Canning, Oliver Goldsmith, Lord Charlemont, and, at first, George Steevens, were among Malone's friends. Encouraged by Charlemont and Steevens, he devoted himself to the study of Shakespearean chronology, and the results of his "An Attempt to Ascertain the Order in Which the Plays Attributed to Shakspeare Were Written" (1778), which finally made it conceivable to try to patch together a biography of Shakespeare through the plays themselves, are still largely accepted. This was followed in 1780 by two supplementary volumes to Steevens's version of Dr Johnson's Shakespeare, partly consisting of observations on the history of the Elizabethan stage, and of the text of doubtful plays; and this again, in 1783, by an appendix volume. His refusal to alter some of his notes to Isaac Reed's edition of 1785, which disagreed with Steevens's, resulted in a quarrel with the latter. Malone was also a central figure in the refutation of the claim that the Ireland Shakespeare forgeries were authentic works of the playwright, which many contemporary academics had believed.

Reviews

(Log in or Create an Account first!)

Details

- Bookseller

- Martin Frost

(GB)

- Bookseller's Inventory #

- FB362 (1 to 3) /4C

- Title

- Theobold's Shakespeare. Volumes 1, 2 & 3.

- Author

- William Shakespeare

- Format/Binding

- Leather binding

- Book Condition

- Used - Good

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Binding

- Hardcover

- Publisher

- C. Hitch, L Hawes.

- Place of Publication

- London

- Date Published

- 1757

- Size

- 11 x17 x3cm

- Weight

- 0.00 lbs

- Note

- May be a multi-volume set and require additional postage.

Terms of Sale

Martin Frost

About the Seller

Martin Frost

About Martin Frost

Glossary

Some terminology that may be used in this description includes:

- Spine

- The outer portion of a book which covers the actual binding. The spine usually faces outward when a book is placed on a shelf....

- Fair

- is a worn book that has complete text pages (including those with maps or plates) but may lack endpapers, half-title, etc....

- First Edition

- In book collecting, the first edition is the earliest published form of a book. A book may have more than one first edition in...

- Title Page

- A page at the front of a book which may contain the title of the book, any subtitles, the authors, contributors, editors, the...

- Gilt

- The decorative application of gold or gold coloring to a portion of a book on the spine, edges of the text block, or an inlay in...