Théophile Gautier. Notice littéraire précédée d'une lettre de Victor Hugo

by BAUDELAIRE Charles & HUGO Victor

- Used

- Fine

- Signed

- first

- Condition

- Fine

- Seller

-

Paris, France

Payment Methods Accepted

About This Item

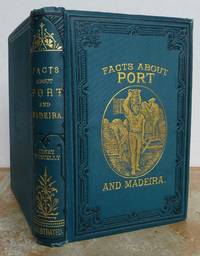

Paris: Poulet-Malassis et de Broise, 1859. Fine. Poulet-Malassis et de Broise, Paris 1859, 11,5x18cm, relié. - | Envois de Baudelaire & Hugo : la tempétueuse rencontre littéraire de l'Albatros et de l'Homme Océan | Édition originale, dont il n'a été tiré que 500 exemplaires. Portrait de Théophile Gautier gravé à l'eau forte par Emile Thérond en frontisipice. Importante lettre préface de Victor Hugo. Reliure en plein maroquin rouge, dos à cinq nerfs sertis de filets noirs, date dorée en queue, gardes et contreplats de papier à la cuve, ex-libris baudelairien de Renée Cortot encollé sur la première garde, couvertures conservées, tête dorée. Pâles rousseurs affectant les premiers et derniers feuillets, bel exemplaire parfaitement établi. Rare envoi autographe signé de Charles Baudelaire?: «?à mon ami Paul Meurice. Ch. Baudelaire.?» Un billet d'ex-dono autographe de Victor Hugo adressé à Paul Meurice à été joint à cet exemplaire par nos soins et monté sur onglet. Ce billet, qui ne fut sans doute jamais utilisé, avait été cependant préparé, avec quelques autres, par Victor Hugo pour offrir à son ami un exemplaire de ses uvres publiées à Paris, pendant son exil. Si l'histoire ne permit pas à Hugo d'adresser cet ouvrage à Meurice, ce billet d'envoi, jusqu'à lors non utilisé, ne pouvait être, selon nous, plus justement associé. Cette exceptionnelle dédicace manuscrite de Charles Baudelaire à Paul Meurice, véritable frère de substitution de Victor Hugo, porte le témoignage d'une rencontre littéraire unique entre deux des plus importants poètes français, Hugo et Baudelaire. Paul Meurice fut en effet l'intermédiaire indispensable entre le poète condamné et son illustre pair exilé, car demander à Victor Hugo d'associer leurs noms à cette élégie de Théophile Gautier fut une des grandes audaces de Charles Baudelaire et n'aurait sans doute eu aucune chance de se réaliser sans le précieux concours de Paul Meurice. Nègre de Dumas, auteur de Fanfan la Tulipe et des adaptations théâtrales de Victor Hugo, George Sand, Alexandre Dumas ou Théophile Gautier, Paul Meurice fut un écrivain de talent qui se tint dans l'ombre des grands artistes de son temps. Sa relation unique avec Victor Hugo lui conféra cependant un rôle déterminant dans l'histoire littéraire. Plus qu'un ami, Paul se substitua, avec Auguste Vacquerie, aux frères décédés de Victor Hugo?: «?j'ai perdu mes deux frères ; lui et vous, vous et lui, vous les remplacez ; seulement j'étais le cadet ; je suis devenu l'aîné, voilà toute la différence.?» C'est à ce frère de cur (dont il fut le témoin de mariage au côté d'Ingres et Dumas) que le poète en exil confia ses intérêts littéraires et financiers et c'est lui qu'il désignera, avec Auguste Vacquerie, comme exécuteur testamentaire. Après la mort du poète, Meurice fondera la maison Victor Hugo qui est, aujourd'hui encore, une des plus célèbres demeures-musées d'écrivain. En 1859, la maison de Paul est devenue l'antichambre parisienne du rocher anglo-normand de Victor Hugo, et Baudelaire s'adresse donc naturellement à cet ambassadeur officiel. Les deux hommes se connaissent assez peu mais partagent un ami commun, Théophile Gautier, avec lequel Meurice travailla dès 1842 à une adaptation de Falstaff. Il est donc l'intermédiaire idéal pour s'assurer la bienveillance de l'inaccessible Hugo. Baudelaire avait pourtant déjà brièvement rencontré Victor Hugo. à dix-neuf ans, il sollicita une entrevue avec le plus grand poète moderne, auquel il vouait un culte depuis l'enfance?: «?Je vous aime comme on aime un héros, un livre, comme on aime purement et sans intérêt toute belle chose.?». Déjà, il se rêvait en digne successeur, comme il lui avoue à demi-mot?: «?à dix-neuf ans eussiez-vous hésité à en écrire autant à [...] Chateaubriand par exemple?». Pour le jeune apprenti poète, Victor Hugo appartient au passé, et Baudelaire souhaitera rapidement s'affranchir de ce pesant modèle. Dès son premier ouvrage, Le Salon de 1845, l'iconoclaste Baudelaire éreinte son ancienne idole en déclarant la fin du Romantisme dont Hugo est le représentant absolu?: «?Voilà les dernières ruines de l'ancien romantisme [...] C'est M. Victor Hugo qui a perdu Boulanger - après en avoir perdu tant d'autres - C'est le poète qui a fait tomber le peintre dans la fosse.?» Un an plus tard, dans le Salon de 1846 il réitère son attaque plus férocement encore, destituant le maître Romantique de son trône?: «?car si ma définition du romantisme (intimité, spiritualité, etc.) place Delacroix à la tête du romantisme, elle en exclut naturellement M. Victor Hugo. [...] M. Victor Hugo, dont je ne veux certainement pas diminuer la noblesse et la majesté, est un ouvrier beaucoup plus adroit qu'inventif, un travailleur bien plus correct que créateur. [...] Trop matériel, trop attentif aux superficies de la nature, M. Victor Hugo est devenu un peintre en poésie?». Ce meurtre du père ne pouvait se réaliser pleinement sans une figure de substitution. C'est Théophile Gautier qui servira de nouveau modèle à la jeune génération, tandis que Victor Hugo, bientôt exilé, ne devait plus publier d'autres écrits que politique pendant près de dix années. Ainsi, lorsque Baudelaire adresse un exemplaire de ses Fleurs du mal à Victor Hugo, il sait qu'il lui inflige cette terrible dédicace imprimée en tête «?Au poète impeccable au parfait magicien ès Lettres françaises à mon très cher et très vénéré maître et ami Théophile Gautier?». L'animosité du jeune poète ne pouvait échapper à Victor Hugo. Et sans doute, Baudelaire ne s'attendait-il pas à la lumineuse réponse d'Hugo?: «?Vos Fleurs du mal rayonnent et éblouissent comme des étoiles?». Avec son article sur Théophile Gautier paru dans L'Artiste du 13 mars 1859, Baudelaire poursuit toujours le même but?: refermer la page «?Victor Hugo?» de l'histoire de la littérature française. Plus adroite et plus respectueuse que ses écrits précédents?: «?Nos voisins disent Shakespeare et Gthe, nous pouvons leur répondre Victor Hugo et Théophile Gautier?!?», la prose de Baudelaire se veut pourtant claire et définitive?: Hugo est mort, vive Gautier, «?cet écrivain que l'univers nous enviera, comme il nous envie Chateaubriand, Victor Hugo et Balzac.?» Les critiques ne s'y trompèrent pas et l'accueil de l'article fut glacial. Baudelaire eut alors l'idée folle d'associer Victor Hugo lui-même à sa propre destitution et de faire ainsi publier sous leur deux noms l'avènement d'une nouvelle ère poétique dont ce fascicule est le manifeste. De son propre aveu, l'impertinent poète avait déjà «?commis cette prodigieuse inconvenance [d'envoyer son article à Victor Hugo sur] papier imprimé sans joindre une lettre, un hommage quelconque, un témoignage de respect et de fidélité.?» Nul doute que le désir de Baudelaire fut alors d'adresser un soufflet à son aîné. L'affaire en serait sans doute restée là sans l'intervention de Paul Meurice. Il informa le fougueux poète de l'appréciation bienveillante du maître qui se serait fendu d'une lettre sans aucun doute aimable mais définitivement perdue. Apprenant cela, Baudelaire rédige à son tour une lettre à Victor Hugo d'une incroyable audace et sincérité?: «?Monsieur, J'ai le plus grand besoin de vous, et j'invoque votre bonté. Il y a quelques mois, j'ai fait sur mon ami Théophile Gautier un assez long article qui a soulevé un tel éclat de rire parmi les imbéciles, que j'ai jugé bon d'en faire une petite brochure, ne fût-ce que pour prouver que je ne me repens jamais. J'avais prié les gens du journal de vous expédier un numéro. J'ignore si vous l'avez reçu ; mais j'ai appris par notre ami commun, M. Paul Meurice, que vous aviez eu la bonté de m'écrire une lettre, laquelle n'a pas encore pu être retrouvée?». Sans fard, il expose ses intentions, ne niant ni l'impertinence de son article, ni la raison profonde de sa demande?: «?J'ai voulu surtout ramener la pensée du lecteur vers cette merveilleuse époque littéraire dont vous fûtes le véritable roi et qui vit dans mon esprit comme un délicieux souvenir d'enfance. [...] J'ai besoin de vous. J'ai besoin d'une voix plus haute que la mienne et que celle de Théophile Gautier, de votre voix dictatoriale. Je veux être protégé. J'imprimerai humblement ce que vous daignerez m'écrire. Ne vous gênez pas, je vous en supplie. Si vous trouvez, dans ces épreuves, quelque chose à blâmer, sachez que je montrerai votre blâme docilement, mais sans trop de honte. Une critique de vous, n'est-ce pas encore une caresse, puisque c'est un honneur???» Il n'épargne pas même Gautier, «?dont le nom a servi de prétexte à mes considérations critiques, je puis vous avouer confidentiellement que je connais les lacunes de son étonnant esprit?». C'est naturellement à Paul Meurice qu'il confie sa «?lourde missive?». Ne doutant pas d'une réponse positive, «?la lettre de Hugo viendra sans doute mardi, et magnifique je le crois?» (lettre à Poulet-Malassis, le 25 septembre 1859), Baudelaire apporte un soin particulier à la mise en valeur du prestigieux préfacier dont le nom sera imprimé dans la même taille de police que le sien. Pourtant la lettre tarde à arriver et c'est encore auprès de Meurice que se plaint Baudelaire?: «?Il est évident que si une raison quelconque empêchait M. Hugo de répondre à mon désir, il me l'aurait fait savoir. Je dois donc supposer un accident.?» (Lettre à Paul Meurice du 5 octobre 1859). En effet, Victor Hugo a bien envoyé sa réponse-préface, elle arrive peu après et Baudelaire la fait intégralement imprimer en tête de son Théophile Gautier. Il ne s'agit pourtant pas d'une simple préface, mais d'une véritable riposte, rédigée avec toute l'élégance du maître. Hugo ne se contente pas des lourds attributs que lui prête Baudelaire qui, dans ce même ouvrage, qualifie ainsi le poète des Contemplations?: «?Victor Hugo, grand, terrible, immense comme une création mythique, cyclopéen, pour ainsi dire, représente les forces énormes de la nature et leur lutte harmonieuse.?» Au manifeste de Baudelaire?: «?Ainsi le principe de la poésie est, strictement et simplement, l'aspiration humaine vers une Beauté supérieure. [...] Si le poète a poursuivi un but moral, il a diminué sa force poétique (..) La poésie ne peut pas, sous peine de mort ou de déchéance, s'assimiler à la science ou à la morale ; elle n'a pas la Vérité pour objet, elle n'a qu'Elle-même.?» Hugo oppose ses propres préceptes?: «?Vous ne vous trompez pas en prévoyant quelque dissidence entre vous et moi. [...] Je n'ai jamais dit l'Art pour l'Art ; j'ai toujours dit l'Art pour le Progrès. [...] Le poète ne peut aller seul, il faut que l'homme aussi se déplace. Les pas de l'Humanité sont donc les pas même de l'Art.?» N'en déplaise à Baudelaire, l'écrivain qu'il rangeait dans les «?délicieux souvenirs d'enfance?» est loin d'avoir achevé son uvre immense. C'est dans ce petit fascicule de l'un de ses féroces adversaires, qu'il annonce la voie de son écriture à venir?: La Légende des siècles, qui doit paraître ce même mois, et surtout trois ans plus tard, Les Misérables, la plus importante fresque sociale et humaniste de la littérature mondiale. Baudelaire adressa des exemplaires dédicacés de son Gautier aux artistes qu'il admirait dont Flaubert, Manet ou Leconte de Lisle, preuve de l'importance qu'il accordait à cette profession de foi esthétique. Malgré sa si précieuse collaboration, Victor Hugo reçut une lettre de remerciements mais aucun exemplaire dédicacé de «?leur?» opuscule. Cependant, une récente étude à la lumière noire a permis de déceler un envoi à son intention «?en témoignage d'admiration?» gratté puis recouvert d'une dédicace palimpseste à M. Gélis. Ce repentir est symbolique de la relation d'amour-haine qu'entretiendront les deux poètes leurs vies durant. C'est donc à travers cet exemplaire offert à «?[s]on ami Paul Meurice » que Baudelaire choisit de remercier le clan Hugo de cette exceptionnelle rencontre littéraire. Le Théophile Gautier de Baudelaire et Hugo est donc, sous son apparente modestie, un double manifeste des deux grands courants de la poésie?: «?L'Albatros?» de Baudelaire, contre l'«?Ultima verba?» de Hugo. Tandis que «?les ailes de géants [du premier] l'empêchent de marcher?», le second «?reste proscrit, voulant rester debout?». Et s'il n'en reste que deux, ce seront ces deux-là?! Provenance?: Paul Meurice, puis Alfred et Renée Cortot. [ENGLISH TRANSLATION FOLLOWS] Théophile Gautier. Notice littéraire précédée d'une lettre de Victor Hugo Poulet-Malassis et de Broise | Paris 1859 | 11.5 x18 cm | full morocco First edition, of which only 500 copies were printed. Portrait of Théophile Gautier etched by Emile Thérond on the frontispiece. Important preface letter by Victor Hugo. Bound in red morocco, gilt date at the foot of spine, marbled endpapers, Baudelairian ex-libris from Renée Cortot's collection glued on the first endpaper, wrappers preserved, top edge gilt. Pale foxing affecting the first and last leaves, beautiful copy perfectly set. Rare handwritten inscription signed by Charles Baudelaire: "" à mon ami Paul Meurice. Ch. Baudelaire. "" (""To my friend Paul Meurice. Ch. Baudelaire."") This exceptional handwritten dedication to Paul Meurice, a real surrogate brother to Victor Hugo, bears witness to a unique literary meeting between two of the most important French poets, Hugo and Baudelaire. Paul Meurice was indeed the essential intermediary between the condemned poet and his illustrious exiled peer, since asking Victor Hugo to combine their names in this Théophile Gautier elegy was one Charles Baudelaire's most daring acts and would, no doubt, not have had a chance of being realised without Paul Meurice's precious support. Paul Meurice, Dumas' ghost-writer, author of Fanfan la Tulipe and the theatre adaptations of Victor Hugo, George Sand, Alexandre Dumas and Théophile Gautier, was a talented writer who was shadowed by the great artists of his time. His unique relationship with Victor Hugo, however, gave him a decisive role in literary history. More than a friend, alongside Auguste Vacquerie, Paul replaced Victor Hugo's deceased brothers: ""I lost my two brothers; him and you, you and him, you replace them; only I was the youngest; I became the eldest, that's the only difference."" It is to this brother at heart (whose marriage he witnessed alongside Ingres and Dumas) that the exile entrusted his literary and financial interests and it is he who he will appoint, along with Auguste Vacquerie, as executor of his will. After the poet's death, Meurice founded the Maison Victor Hugo, which is still today one of the writer's most famous residences. In 1859, Paul's house then became Victor Hugo's Parisian antechamber on the Anglo-Norman rock, and so naturally Baudelaire went to speak to this official ambassador. The two did not know each other well but they had a mutual friend, Théophile Gautier, with whom Meurice had worked since 1842 on an adaptation of Falstaff. Consequently, he is the ideal intermediary to guarantee the inaccessible Hugo's benevolence. Baudelaire had, however, already briefly met Victor Hugo. At the age of 19 he asked for an interview with the greatest modern poet, whom he had worshiped since childhood: ""I love you as one loves a hero, a book, as one loves everything beautiful purely and without interest."" He already dreamed of himself as a worthy successor, as he tacitly confessed to him: ""at nineteen years old would you have hesitated over writing as much to [...] Chateaubriand for example?"" For the young apprentice poet, Victor Hugo belonged to the past, and Baudelaire will quickly want to free himself of this heavy model. From his first work, Le Salon de 1845, the iconoclast Baudelaire criticized his old idol by declaring the end of Romanticism, of which Hugo is the absolute representative: ""These are the last ancient ruins of romanticism [...] It is Mr Victor Hugo who lost Boulanger - after having lost so many others - It is the poet who caused the painter to fall into the pit."" One year later, in Le Salon de 1846 he reiterated his attack even more fiercely, removing the Romantic master from his throne: ""because if my definition of romanticism (intimacy, spirituality, etc.) puts Delacroix at the head of romanticism, it naturally excludes Mr Victor Hugo. [...] Mr Victor Hugo, whose nobility and majesty I certainly do not want to diminish, is a much more skilful rather than inventive worker, a much more correct rather than creative worker. [...] Overly material, overly attentive to nature's appearance, Mr Victor Hugo has become a painter by poetry."" This murder of the father could not be fully realised without a substitute figure. It is Théophile Gautier who will serve as the new model for the young generation, whereas Victor Hugo, soon to be exiled, will no longer publish anything other than political writing for almost ten years. So, when Baudelaire addressed a copy of his Fleurs du Mal to Victor Hugo, he knew that he was inflicting on him this terrible dedication printed at the top ""To the impeccable poet to the perfect magician of French letters to my very dear and very revered master and friend Théophile Gautier."" The young poet's animosity could not have escaped Victor Hugo. And no doubt Baudelaire did not expect this bright answer from Victor Hugo: ""Your Fleurs du Mal radiate and dazzle like the stars."" With his article on Théophile Gautier published in L'Artiste on 13 March 1859, Baudelaire always pursues the same goal: to turn the ""Victor Hugo"" page of the history of French literature. More skilful and more respectful than his previous writing: ""Our neighbours talk of Shakespeare and Gthe, we can respond to them with Victor Hugo and Théophile Gautier!"", Baudelaire's prose is intended to be clear and definitive: Hugo is dead, long live Gautier, ""this writer for whom the universe will envy us, as it envies us Chateaubriand, Victor Hugo and Balzac."" The critics were not mistaken and the article's reception was icy. Baudelaire then had the crazy idea of involving Victor Hugo himself in his own removal and publishing, under their two names, the arisen of a new poetic era, of which this booklet is the manifesto. By his own admission, the impertinent poet had already ""committed this tremendous impropriety [of sending his article to Victor Hugo on] paper printed without enclosing a letter, a given tribute, a testimony of respect and loyalty."" There is no doubt that Baudelaire wanted to deliver a blow to his elder. The matter would certainly have persisted without Paul Meurice's intervention. He informed the hot-headed poet of the master's benevolent appreciation, who would have responded with an undoubtedly kind, but definitively lost letter. Learning this, Baudelaire in turn wrote an incredibly audacious and sincere letter to Victor Hugo: ""Sir, I greatly need you, and I invoke your kindness. Several months ago, I wrote a fairly long article about my friend Théophile Gautier which caused such laughter amongst fools that I saw it fit to make it into a little brochure, if only to prove that I never repent. - I requested the people at the newspaper send you a copy. I do not know if you have received it; but I learnt from our mutual friend Mr Paul Meurice, that you were good enough to write me a letter, which has not yet been found."" He plainly reveals his intentions, denying neither the impertinence of his article, nor the profound reason for his request: ""I especially wanted to bring the reader's thought back to this marvellous literary era of which you were the true king and which lives in my mind as a delicious memory of childhood. [...] I need you. I need a louder voice than mine and than that of Théophile Gautier, - your dictatorial voice. I want to be protected. I will humbly print what you deign to write to me. Don't be shy, I beg you. If you find something to blame in these tests, know that I will show your condemnation obediently, but without too much shame. Your criticism, is it not yet a caress, because it is an honour?"" He did not spare even Gautier, ""whose name served as a pretext to my critical considerations, I can confess confidentially that I knew the shortcomings of his surprising mind."" Naturally, Baudelaire entrusts his ""heavy missive"" to Paul Meurice. Not doubting a positive response, ""Hugo's letter will undoubtedly come Tuesday, and magnificent I believe it"" (letter to Poulet-Malassis, 25 September 1859), Baudelaire takes particular care to highlight the prestigious preface writer, whose name will be printed in the same font size as his own. However, the letter is slow to arrive and it is again to Meurice that Baudelaire complains: ""It is obvious that if any reason prevented Mr Hugo from meeting my request, he would have let me know. I must then assume an accident."" (Letter to Paul Meurice on 5 October 1859). Indeed, Victor Hugo had sent his preface-response, it arrives shortly after and Baudelaire fully prints it at the head of his Théophile Gautier. It was not, however, a simple preface, but a real response, written with all the master's elegance. Hugo is not satisfied with the heavy attributes that Baudelaire offers him, Baudelaire who, in this same work, so describes the poet of Contemplations: ""Victor Hugo, great, terrible, vast like a legendary creation, cyclopean, so to speak, represents the enormous forces of nature and their harmonious struggle."" To Baudelaire's manifesto: ""Thus the principle of poetry is, strictly and simply, human aspiration towards a superior Beauty. [...] If the poet pursues a moral goal, he diminishes his poetic force (..) Poetry can not, under pain of death or decline, fit in with science or morality; it does not have the Truth as its object, it only has Itself."" Hugo opposes his own precepts: ""You are not mistaken in foreseeing some dissidence between you and me. I never said Art for Art; I always said Art for Progress. [...] The poet can not go alone, he needs man also to travel. The footsteps of humanity are therefore the same as the footsteps of Art."" With all due respect to Baudelaire, the writer that he categorised in the ""delicious memories of childhood"" is far from having completed his vast work. It is in this little booklet of one of his fierce adversaries, that Hugo announces the path of his future writing: La Légende des siècles, which should appear this same month, and certainly three years later, Les Misérables, the most important social and humanist saga in world literature. Baudelaire addressed the dedicated copies of his Gautier to artists that he admired including Flaubert, Manet and Leconte de Lisle, proof of the importance that he granted to this profession of aesthetic faith. Despite his so precious collaboration, Victor Hugo received a letter of thanks but no copy dedicated to ""their"" pamphlet. However, a recent study in black light made it possible to detect a scratched out presentation intended ""in testimony of admiration"", then covered with a palimpsest dedication to Mr Gélis. This remorse is symbolic of the love-hate relationship that these two poets will maintain throughout their lives. Therefore, it is through this copy offered to ""his friend Paul Meurice"" thatBaudelaire choses to thank the Hugo clan for this exceptional literary meeting. Baudelaire and Hugo's Théophile Gautier is therefore, under his apparent modesty, a double manifesto of the two great poetry powers: L'Albatros by Baudelaire, against Ultima verba by Hugo. While ""the wings of the giants [of the first] prevent him from walking,"" the second ""remains forbidden, wanting to remain standing."" And if only two remain, it will be these two here! An ex-dono handwritten note by Victor Hugo addressed to Paul Meurice has been attached to this copy by us and guarded. This note, which was no doubt never used, had however been prepared by Victor Hugo with several others, to offer this friend a copy of his works published in Paris during his exile. If history does not allow Hugo to address this work to Meurice, this presentation note, until now unused, could not, in our opinion, be more justly united. Provenance: Paul Meurice, then Alfred and Renée Cortot.

Reviews

(Log in or Create an Account first!)

Details

- Bookseller

- Rare Books Le Feu Follet - Edition-Originale.com

(FR)

- Bookseller's Inventory #

- 68622

- Title

- Théophile Gautier. Notice littéraire précédée d'une lettre de Victor Hugo

- Author

- BAUDELAIRE Charles & HUGO Victor

- Book Condition

- Used - Fine

- Publisher

- Poulet-Malassis et de Broise

- Place of Publication

- Paris

- Date Published

- 1859

- Bookseller catalogs

- Literature;

Terms of Sale

Rare Books Le Feu Follet - Edition-Originale.com

Librairie Le Feu Follet accepts Visa and Mastercard, as well as PayPal and French checks. We have made every effort to describe our books as accurately as possible. However, any item may be returned within 30 days after delivery, in the same condition, if they turn out not as described. Please inform us first, by e-mail or phone, specifying the problem. Our email is always available for your convenience. We ship by air whenever possible.

About the Seller

Rare Books Le Feu Follet - Edition-Originale.com

Biblio member since 2004

Paris

About Rare Books Le Feu Follet - Edition-Originale.com

Rare Books Le Feu Follet brings together a wide range of hard to find, valuable rare books, including incunables, manuscripts, limited first editions, fine bindings, inscribed books and autographs. Over 25.000 books in all the fields of knowledge: literature, science, history, art, esoterica, philosophy, travel and more. Our books are searchable by field of interest. We also give expert advice and buy rare books - from a single volume to a set or even en entire collection.

Glossary

Some terminology that may be used in this description includes:

- Spine

- The outer portion of a book which covers the actual binding. The spine usually faces outward when a book is placed on a shelf....

- Top Edge Gilt

- Top edge gilt refers to the practice of applying gold or a gold-like finish to the top of the text block (the edges the pages...

- FOI

- former owner's intials.

- New

- A new book is a book previously not circulated to a buyer. Although a new book is typically free of any faults or defects, "new"...

- Fine

- A book in fine condition exhibits no flaws. A fine condition book closely approaches As New condition, but may lack the...

- Wrappers

- The paper covering on the outside of a paperback. Also see the entry for pictorial wraps, color illustrated coverings for...

- Leaves

- Very generally, "leaves" refers to the pages of a book, as in the common phrase, "loose-leaf pages." A leaf is a single sheet...

- Morocco

- Morocco is a style of leather book binding that is usually made with goatskin, as it is durable and easy to dye. (see also...

- First Edition

- In book collecting, the first edition is the earliest published form of a book. A book may have more than one first edition in...

- Gilt

- The decorative application of gold or gold coloring to a portion of a book on the spine, edges of the text block, or an inlay in...